Reading guide to Maurice Sendak

Maurice Sendak’s best known work is the picture book "Where the Wild Things Are". When it was published in 1963, it immediately sparked a debate: was it really suitable for young children? The pleasure of the book lies in Sendak’s radical and refined “picture-book narrative”, where text and image share the task of driving the story forward – sometimes information is contained in the thirteen short sentences of text, and at other times the picture and its change in size are all it takes to convey Max’s feelings.

About the reading guide

This reading guide is written by Ulla Rhedin, former member of the jury for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. Our reading guides are to be used in book circles, in schools or just as inspiration for further reading.

About the author

Born in 1928, Maurice Sendak grew up in Brooklyn, New York, the youngest child of Polish Jewish immigrants. He has described how on Sundays the family would be invaded by relatives who not only brazenly ate them out of house and home, but also insisted on hugging and kissing the children while noisily proclaiming their kinship. It is perhaps no surprise that he soon came to describe childhood as “a range of humiliation”. He also described childhood as a state of being in which the child must constantly overcome boredom, fear, pain, anxiety and loneliness, declaring “it is a constant miracle to me that children manage to grow up.” Maurice Sendak died on 8 May 2012 at the age of 83.

About the book

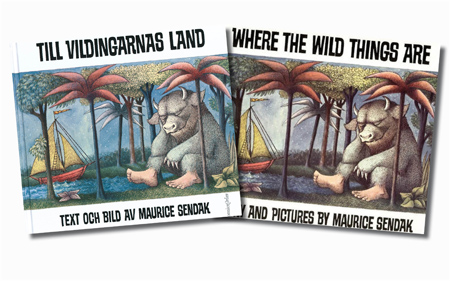

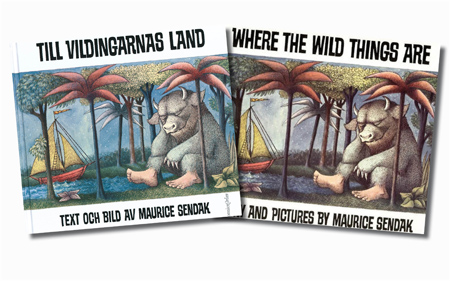

By far Sendak’s best known work is the picture book Where the Wild Things Are. When it was published in 1963, seven years after his debut work, it immediately sparked a debate: was it really suitable for young children? Wouldn’t it scare them? Do them harm? None of the child psychologists whose views were sought wanted to ban the book, but many parents over the years have rejected it as far too frightening. Since its original issue, it has been widely reprinted and translated.

The book is about a boy called Max who, dressed in his wolf suit, makes “mischief of one kind and another” until his mother can take no more and sends him to bed without his supper. Max stands in his bare room, more angry than upset, and decides to run away. The reader watches as his room transforms into a jungle, his bed becomes a boat and he sails away to where the wild things are. Once there, he is made king and forces the creatures to take part in a “wild rumpus” before sending them to bed without their supper. He then starts feeling homesick, so he waves goodbye to the wild things and returns to his normal room, where his supper is waiting for him. The keen reader will notice that Max now has more “breathing space”: the pictures grow in size through the book and then return to a “reasonable” size compared with the rather cramped image on the first page.

The pleasure of the book lies in Sendak’s radical and refined “picture-book narrative”, where text and image share the task of driving the story forward – sometimes information is contained in the thirteen short sentences of text, and at other times the picture and its change in size are all it takes to convey Max’s feelings.

On October 16, 2009, the world premiere of Spike Jonze’ long-awaited film version of Sendak’s internationally renowned book took place. Five years in production, the film was made with Sendak’s blessing and he had some involvement in the project as one of the producers. The plot is essentially the same, but of course a few additions had to be made to create a 101-minute feature film from a picture book. In the book, it is clear that Max is no more than about four years old at most, and the conflict is perhaps more of an unfortunate misunderstanding on the part of a tired mother than an actual conflict over discipline. In the film, he has been made nine or ten years old, he has a bossy big sister and a single mother, who has started bringing home her new male friend. The conflict here is much more powerful and explosive. However, Max’s frustration, loneliness and rage are much the same.

The wild things also share the same function – being fundamentally dangerous but allowing themselves to be controlled by Max, and the film’s seven hairy wild things each reflect a character trait in Max: the hot-tempered friend Carol (with the voice of James Gandolfini) represents Max’s inner struggle, the bull is an outsider like Max, another of the wild things personifies his suspicion and negativity and so on.

The film was met with great enthusiasm by many US critics and – just like when the book was released in 1963 – with concern, anxiety and fascination by a host of parents. But for children from six or seven up it is certainly an experience.

Things to think about after reading Where the Wild Things Are

Start by looking at the cover: what does it tell you about the content of the book?

Study the title page: who is afraid of whom?

Compare the first and last pictures in the book: how does Max feel in both pictures?

We never get a glimpse of Max’s mother in any of the pictures. What does this omission do to the way we interpret what happens?

The sea monster that appears behind Max as he sails away is never mentioned in the text: why do you think that is?

After the wild rumpus, Max sends the wild things to bed without any supper. What has happened to him here?

In the final scene, Max’s supper is waiting for him. What does that mean?

Note the way the moon changes as the book proceeds. How long is Max away? What might the moon symbolise as well as the passage of time?

Further reading on Where the Wild Things Are

Ulla Rhedin: Bilderboken – på väg mot en teori, sthlm 1991, 2001 (in Swedish)

Lanes, S., The art of Maurice Sendak. New York 1980

Nicholson, A., Where the Wild Things Are. “As untameable as the original”, Movie Reviews, 12 October 2009. Web: boxoffice.com/reviews/2009

Learn more

You can find much more information about Maurice Sendak and all our laureates at alma.se.

Share your ideas

Would you like to share the ways you’ve discussed or worked with Where the Wild Things Are? E-mail us at litteraturpris@alma.se and we can share your ideas on our website, alma.se. Let’s build a store of knowledge and inspiration together!

Children have the right to great stories

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories. This global award is given annually to a person or organisation for their outstanding contribution to children’s and young adult literature. With a prize of five million Swedish kronor, it is the largest award of its kind. Above all else, it highlights the importance of reading, today and for future generations. Find more information at alma.se