Reading guide Ryôji Arai

In Basu ni notte a little boy is waiting for a bus. As he waits, doing nothing, unlikely enough the “whole world” appears in a long parade before his eyes and when the bus finally arrives, after several days, it’s full!

In Basu ni notte a little boy is waiting for a bus. As he waits, doing nothing, unlikely enough the “whole world” appears in a long parade before his eyes and when the bus finally arrives, after several days, it’s full!

This reading guide was written in 2012 by Ulla Rhedin, former member of the jury for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award. Our reading guides are to be used in book circles, in schools or just as inspiration for further reading.

Ryôji Arai (born in 1956 in Yamagata in Japan) is the second illustrator to receive the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award (2005). It was a picture of a moon man in pyjamas from the award-winning Japanese book of riddles Nazo nazo no tabi (1998, our translation: A Journey with Riddles, with text by Chihirō Ishizu) that first caused Ryôji Arai to catch the jury’s eye. The picture was reproduced in a catalogue from the Children’s Book Fair in Bologna, and was to illustrate the riddle “A round face that gradually gets smaller before becoming round again”. With its refined naivety the illustration revealed a rich and unpredictable picture book narrative.

It also proved to contain a number of features typical of Arai. The way the scene is set gives the impression of being part of the audience in a theatre. The characteristic Japanese landscape with its pointed, volcanic mountains can be seen in the background. There are winding roads, a sea in the distance, fish in the lake, planets, stars and various flying creatures in the sky, and not least, strangely personified objects, such as wandering appliances and telegraph posts. Despite being set at night, the picture is surprisingly colourful with its clear green landscape in saturated gouache.

The man behind the image was a picture book artist, still quite young yet with a large and varied body of work behind him, and about a dozen of his books were extremely good indeed. One of Arai’s most striking features was his consistent child’s eye view, in other words seeking to always tell the story from the eye level of a small child, combined with a kind of relaxed, unremarkable, naive style, in text and pictures, in the many books he produced entirely alone.

Ryôji Arai always starts by allowing the text to struggle its way through, after which creating the pictures goes quite quickly. “I want to make my pictures simple and a little rough,” he said in one interview, “so that the child can feel that they might be able to do almost the same thing”. To achieve this spontaneous, naive expression, he often paints with the wrong hand: “Sometimes I use both hands at the same time and without brushes, that is good because then both halves of the brain have to keep working!” Arai admits that sometimes he goes so far as to even paint pictures with his head – constantly seeking to avoid the perfect, “adept”, superior form of expression that he thinks everyone who is trained as an illustrator risks ending up with.

Other ways of avoiding this trap are to constantly think out new picture solutions, make things difficult for yourself, dramatise every new spread so that there is a surprise or at least something unexpected there to discover. It must never be stylish and proficient, the unruly elements of the process should instead be in plain sight, by allowing abandoned lines to remain almost visible, for example.

Arai points out that, as Japanese people traditionally do, he values emptiness, the unsaid, the pause or the space in actions and in the relationships between text and pictures. One of his most special picture books is precisely about a charged empty space A Forest Picture Book (original title: Mori no ehon, 1999) based on a poem by Hiroshi Osada. It is a poetic, endless dialogue between a listening “I” and a disembodied voice. The voice reminds the reader of the beauty in life, about love and the secretive nature of the forest. Arai never gives the voices a body but has the conversation depicted in a number of tableaux that all take place in an exquisitely beautiful forest.

Another way in which Arai achieves this charged empty space is by using a dramaturgy lacking tension, conflicts, escalation or high points. In Yukkori to Jojoni, (1991, our translation: Calm and A-bit-at-a-time) a boy and a girl with these names meet and walk part of the way together before they separate. Again, in Happi-san (2003) nothing particular happens to the main characters, who are going to ask Mr Happy a question each but he never appears. Both are still satisfied, but for completely different reasons than they had imagined. Arai’s books end like this surprisingly often, with everything being OK, we are fine as we are, we may as well take it easy so as not to miss the beauty that surrounds us. It is more about playfulness, brief encounters and about having a relaxed attitude to life.

Arai says that in his picture books he wants to be a kind of opposing force to the quite rigid and organised Japanese society, where children are expected to follow the rules laid down and be trained to fit in from an early age. He himself was never happy at school and preferred to sit at home for long periods of time and draw by himself. In the light of this, it is easy to understand that his friendly, sympathetic and child-focused stories play an important role in Japan and are much appreciated by children and adults there.

Arai is very prolific and since his debut in the mid-1980s has produced about a hundred picture books – baby books, nonsense picture books, fairytale picture books – illustrating works by other authors and poets and creating books that are entirely his own work. Since 2006 he has been drawing an animated TV series for children, Sukima no: Kuni no: Polta (Polta: The Land Between the Worlds), which has been a huge success in his homeland.

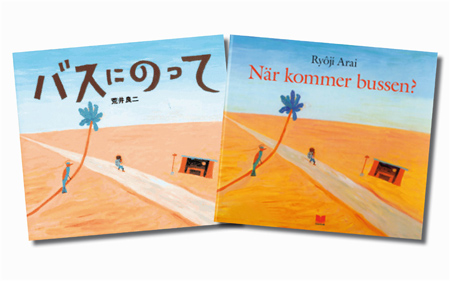

Two of Arai’s own picture books have so far been translated into Swedish (2006), Basu ni notte (1992) and Sûsû to Neruneru (1996) The latter displays his talents as an excellent colourist, a fantasy picture book or a dream nonsense adventure where anything could happen.

In Basu ni notte a little boy is waiting for a bus. Here Arai wanted to experiment with a constant horizon. To achieve this, he chose a desert landscape, sand and sky, that he tips in different diagonals as the young main character, the narrator, vainly waits and waits for a bus in a little bus shelter with the company of nothing but the music from a transistor radio. As he waits, doing nothing, unlikely enough the “whole world” appears in a long parade before his eyes. Arai calls this idea “A theatre in reverse”.

But when the bus finally arrives, after several days, it’s full! The boy waits a little longer and then puts his big pack on his back and starts to walk. That’s all there is!

The book can be categorised as a concept picture book, which can have a wider use in all sorts of educational contexts. These build on a simple basic idea, a type of never-ending situation, which then endlessly develops. They can inspire storytelling by adding new episodes about other animals and vehicles passing the waiting main character.

The book can be compared with other concept picture books, such as Anna-Clara Tidholm’s Knacka på!, Kitty Crowther’s Alors?, Ernst Jandl & Norman Junge’s Next Please, Håkan Jaensson & Gunna Grähs’ Rita ensam hemma, Håkan Jaensson & Gunna Grähs’ Jag såg, jag ser and Hur blir det då? and Anna Hingström’s Måste ha mer!

The action of the book can inspire philosophical conversations about abstract things such as “the passing of time”, “waiting”, “patience” etc. and about “everything not being how you expected”. What sort of journey is he on? How has he got there and where is he going? Who sits and waits for a bus in the middle of the desert? What would happen if I was to sit there?

What is the effect of Arai choosing the desert as a setting?

Why does Arai make the lorry and the bus enormous vehicles? How does he convey the size of the cars and the high speed in the pictures?

The book is also about the importance of music. What role does it play in his experiences? How can you see what music he is listening to in the pictures? How do both of the crowded pictures differ from the others in the book? Might the big parades only be happening in his imagination?

What musical instruments are there?

Compare the book with other books about waiting and the passing of time or strange journeys, such as Kitty Crowther’s Alors?, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, Ernst Jandl & Norman Junge’s Next Please, Håkan Jaensson & Gunna Grähs’ Rita ensam hemma, Thomas & Anna-Clara Tidholm’s Resan till Ugri-La-Brek, Vill ha syster and Förr i tiden in skogen, Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Anna Höglund’s Resor jag aldrig gjort, and Eva Lindström’s Jag rymmer and I skogen.

Use the simple episodic structure, naive pictures and strong colours of the book as the starting point for telling your own stories. What would happen if the book were set in a completely different setting, in another country and with another main character? What encounters might happen then?

The book can be turned into a project. What would happen if I was to sit there? What would my music be like?

Other books about meetings, such as Gunna Grähs’ Tutu och tant Kotla, Tutu och lilla Kurren, Syrma och Tocke Broms, Mehmet och lilla Luna (Hejhej-böckerna), Sara Lundberg’s Vita Streck och Öjvind, Shaun Tan’s The Arrival and Thomas & Anna-Clara Tidholm’s En som du inte känner.

Rhedin, Ulla, ‘Djärv, fräck och oförutsägbar’ – Ryoji Arai, en japansk kolorist på barnens villkor, Opsis Kalopsis nr 4 2005 (pp. 4-11) (in Swedish).

Rhedin, Ulla, Tankar om bilderboksillustration, Tecknaren nr 5 2005 (pp.18-27) (in Swedish).

You can find much more information about Ryôji Arai and all our laureates at alma.se.

Would you like to share the ways you’ve discussed or worked with Basu ni note? E-mail us at litteraturpris@alma.se and we can share your ideas on our website, alma.se. Let’s build a store of knowledge and inspiration together!

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories. This global award is given annually to a person or organisation for their outstanding contribution to children’s and young adult literature. With a prize of five million Swedish kronor, it is the largest award of its kind. Above all else, it highlights the importance of reading, today and for future generations. Find more information at alma.se