A doorway to the marvellous

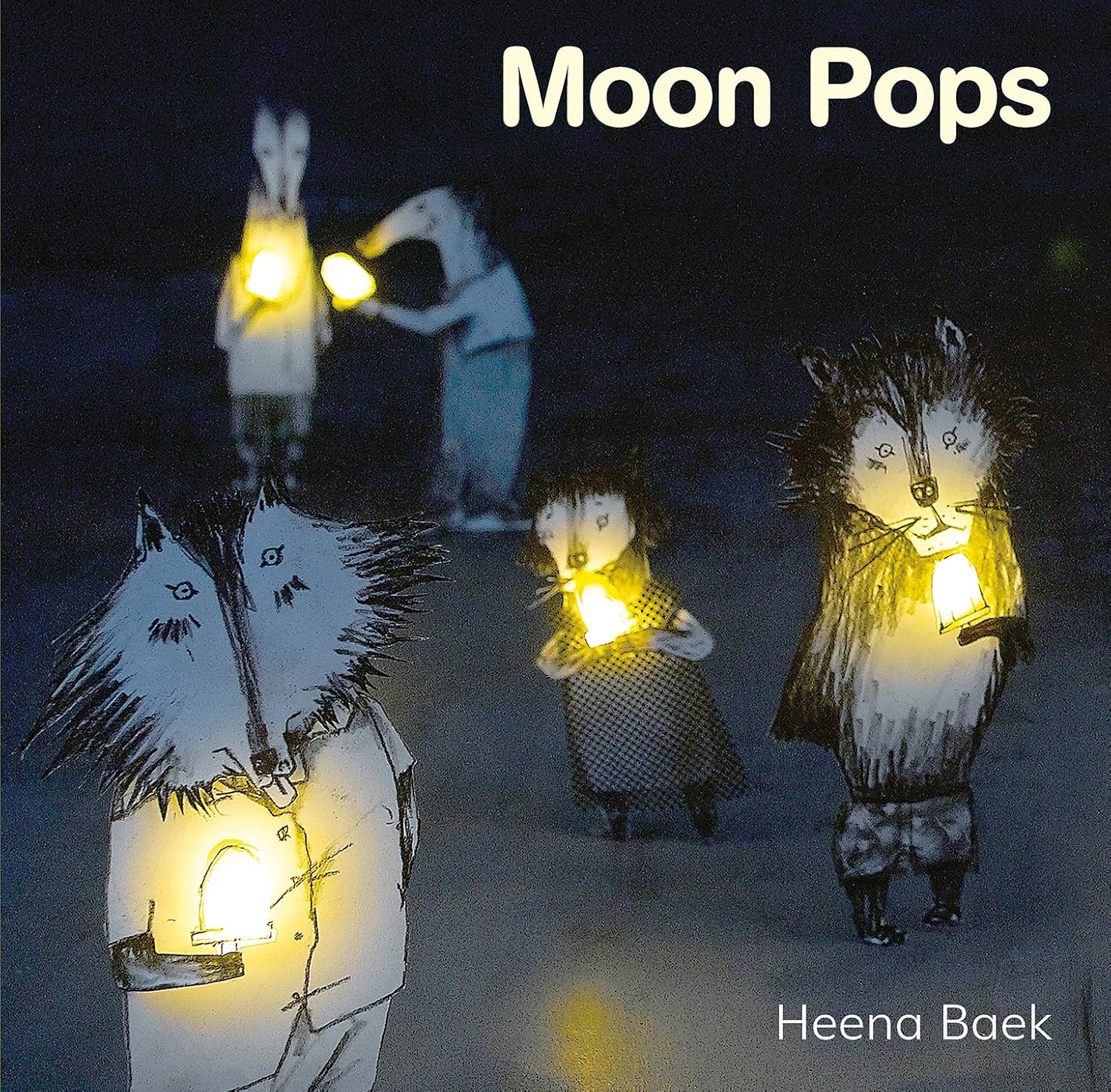

Baek Heena’s picture book worlds open the door to magic and wonder. With a background in film animation, her unique visual style features handmade miniature figurines and environments painstakingly lighted and photographed.

Photo: Elliot Elliot

Photo: Elliot ElliotQuick facts

The jury’s motivation

With exquisite feeling for materials, looks and gestures, Baek Heena’s filmic picture books stage stories about solitude and solidarity. In her evocative miniature worlds, cloud bread and sorbet moons, animals, bath fairies and people converge. Her work is a doorway to the marvellous: sensuous, dizzying and sharp.

Baek Heena was born in 1971 in Seoul. After working in advertising and multimedia for children, she began to create her own picture books when her daughter was born.

Baek Heena’s picture book worlds open the door to magic and wonder, and her original techniques and artistic solutions breathe new life into the picture book medium. Her bookmaking is a time-consuming process requiring devoted attention to construction and sculpture as well as lighting design.

The child’s perspective runs through all of Baek Heena's books, as does an unshakeable belief in the power of play and imagination in our lives.

An unshakeable belief in the power of play and imagination

This text was written in 2020 by Elina Druker and Maria Lassén-Seger.

Please note that the titles of published books used on the website are not the original titles; they are the titles used by Baek Heena’s publisher in its international marketing.

Baek Heena is a multi-award-winning Korean picture book artist. She was born in Seoul in 1971. The majority of her thirteen picture books are illustrated with her own intricately crafted miniature figures and environments, carefully lit and photographed. Baek has a background in animated film and studied at Ewha Womans University in Seoul and at the California Institute of the Arts. After working in advertising and multimedia for children, she turned to creating her own picture books when her daughter was born.

What happens when you eat bread baked of clouds? In her first book, Gu-reum-bbang (2004, Cloud Bread), Baek demonstrates innovation and a desire to find new modes of visual expression. The book’s central characters (a family of cats), their home and the outdoor environments are all fabricated of paper and cardboard, lit and photographed by Hyang Soo Kim. The contrast between the flat paper figures and the three-dimensional spaces creates a dynamic, magic world that draws viewers irresistibly into the story.

Gu-reum-bbang takes place on a rainy weekday morning, when two kittens find a little cloud and take it home. Their mother uses the cloud to bake bread, which they eat for breakfast. Not only is the bread delicious, it also makes everyone who eats it turn light as a cloud and gives them the ability to fly. This comes in handy for the kittens, who use the magic power of the moon bread to rescue their father from a work-related scrape. The book is narrated by the little girl of the family and leans into the world of make-believe and play. The cloud bread symbolizes to great effect the miracles that happen every day when we care for one another.

Since her debut, Baek Heena has continued to evolve a singular and highly original picture book world. Within that world, she constructs stories very much like theater pieces, building environments like stage sets and using lighting to great effect. Her techniques connect to a long tradition of toy books for children—a genre to which Baek has brought development and renewal with her highly original technical and artistic solutions.

Baek’s early picture books show a fascination with dollhouse-like environments, populated with flat figures cut from paper or dolls sewn of cloth. Dal Sha-bet (2011, Moon Sherbet) is set in an apartment building on a sweltering summer’s night, so hot that the heat wakes up the residents. When the moon itself begins to melt, and the overstrained air conditioning causes a power outage, the residents can enjoy moon sherbet that grants them relief from the heat and cool, peaceful dreams. Baek allows her creativity free rein, taking dollhouse play to new heights and giving readers a peep into all the residents’ apartments, each one individually decorated and arranged. We can nearly see the heat of the night in the contrasts between oppressive dark and flickering lights, nearly hear it in the drip-drip of the melting moon, the drone of air conditioning and the hum of refrigerators. Baek’s picture book world is astonishing not only in its wealth of visual detail, but also in its ability to enfold the reader in an experience for all the senses.

Baek Heena often draws attention to the book as a spatial and material form. Her technique recalls the peep-box or the diorama, where objects arranged within a box or a glass case create a miniature scene in perspective. Baek herself has mentioned Hitchcock’s Rear Window as an inspiration for Cloud Bread, and the concept reappears in her treatment of the apartment buildings in Dal Sha-bet. Uh-je-jo-nyeok (2012, Last Night)—similarly set in an apartment building —takes the form of a fold-out book, reinforcing the linkages between the apartments and lives that appear in the story.

Each panel takes the reader into a new home and shows a snapshot of the everyday routines, problems, and relationships of the people who live there. As the book shows, all of them, despite individual differences, belong together and have more in common than they might imagine. The themes of the dollhouse and handcraft truly come to the fore in this book, whose characters seem proud to be identifiable as handmade, three-dimensional dolls. Mr. Zebra’s body is sewn of striped cotton; his neighbors Mr. and Mrs. Dog boast button eyes and visible stitching. They are shabby, lopsided, and misshapen, but it is these imperfections that give them much of their charm.

In later books—such as Jang-su-taang seon-nyeo-nim (2012, Bath Fairy), Al-sa-taang (2017, Magic Candies) and Na-neun ghe-dah (2019, I Am a Dog), Baek Heena’s characters become even more expressive. They have firm bodies sculpted from clay, accentuating their anatomy, body language and facial features. The settings, too, evolve toward a more animated and cinematic style, using varied lighting, visual depth and spatiality in a highly innovative way for the picture book as a medium. The process of creating each book is long and laborious. To achieve a range of gestures, physical appearances, and postures for each of her characters, Heenas crafts multiple small clay figures in different variants and in different poses, and then paints and dresses each of them.

Baek Heena has said that she finds inspiration in the craft process itself, and a creative challenge in the picture book format and the constraints of two-dimensional image-making. Her dedication to the manual process, the sculpting and the lighting, and her attention to the tiniest detail, are not only impressive but also crucial to the finished result. This might mean making scores of copies of a single character with only miniscule variations in posture or facial expression, hand-sewing tiny articles of clothing, manufacturing miniature shoes, or hand-printing wallpapers that we will never more than glimpse on the wall of a room in the background of a story.

For all the care she lavishes on her characters, Baek devotes equal attention to the environments they inhabit. She opens and extends space in a way reminiscent of animated film. At the same time, she uses lighting to define spaces and create an atmosphere that is distinctive, inviting, and intimate. Alternating rhythmically between close-ups and long shots, her visuals are typically designed around the experience of the child character. In Bath Fairy, a little girl goes to the baths, where she meets a mysterious old lady who turns out to be a bath fairy. The book does full justice both to Baek’s sense of the slapstick and to the capacity of children for wholehearted experience. The sheer physical pleasure of sliding into cool water or lounging in a hot bath is captured to perfection. Naked bodies, young and old, are pictured matter-of-factly and with nuance. The joyful scene when old woman and little girl dive under the water together is one of the highlights of the book.

Baek Heena populates her picture books with dolls and animals with human qualities. Although the majority of her books focus on children and convey the child perspective, she also portrays adults and the elderly with refinement and humor. Bath Fairy is one example; another is Pat-juk hal-mum-ghwa ho-rang-ee (2006, Red Bean, Granny and the Tiger), with author Yun-kyu Park. For this story, based on a Korean folk tale, Baek crafted her expressive figures from hanji, the traditional Korean paper made from mulberry bark. In Dal Sha-bet, the main character is an old lady wolf. She is the one who takes the lead and catches the drops of the melting moon in a bowl to make magical cooling sherbet for everyone in the building. And it is she who makes the moon return so that the homeless moon rabbits—familiar figures in Asian folktale and myth—can come home again. There is, in other words, a strong interconnection between the generations in Baek Heena’s books, as well as a living interest in exploring and incorporating the ingredients of literary tradition.

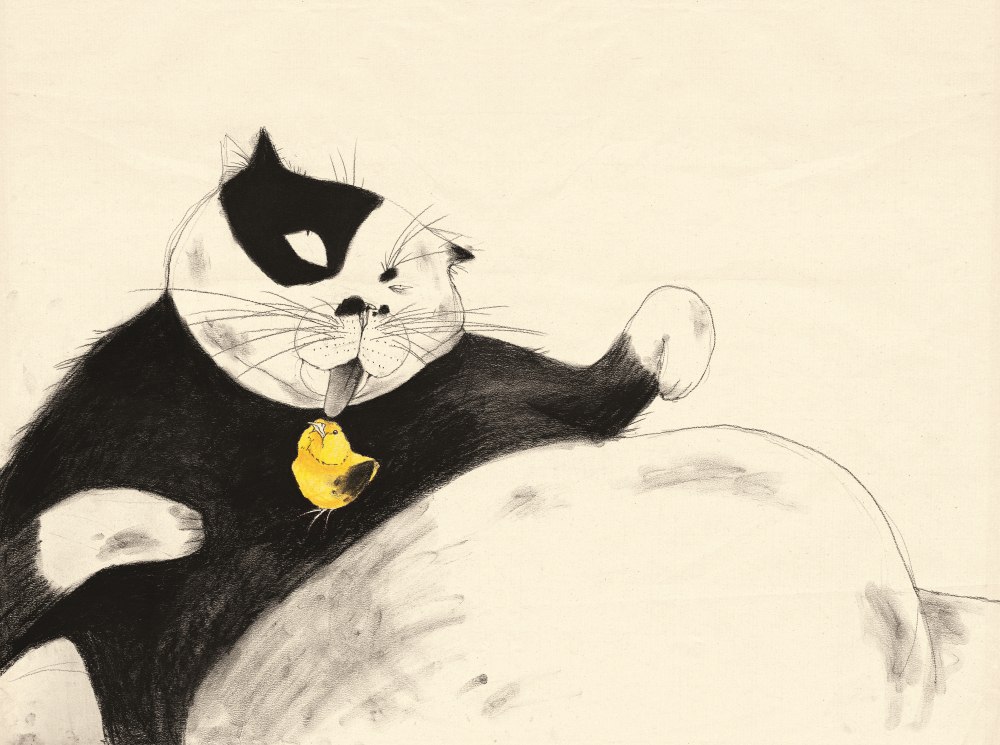

Baek’s picture book worlds open the door to magic and wonder. Nowhere is this more true than in Pi-ya-ghi Eomma (2011, Little Chick Pee-yaki’s Mum), one of just a few books in her oeuvre that is drawn in charcoal and ink. This crazy, quirky tale paints a portrait of parenthood that is both candid and comedic. A cat named Mjahau lives to hunt down, torment and eat up small animals. One day, however, Mjahau swallows a chicken egg and is amazed to give birth to a baby chick. This unlikely event leads to an equally unlikely transformation in Mjahau, who finds a new role in life after accepting responsibility for sheltering and raising little Pee-yaki.

An elevated, enchanted everyday is often a core element in Baek Heena’s stories. In combination with a tight focus on the individual perspective, she crafts stories that draw readers into the emotional lives of her characters. This is particularly the case in Al-sa-taang (Magic Candies), about a young boy named DongDong whose life takes a decisive turn when he stumbles upon some magical sweets that give him the power to hear and speak to animals, inanimate objects, and his dead grandmother. The story takes the form of an interior monologue by DongDong, underlining the connections between the magical events of the story and his emotional processes. In a subtle and open-ended manner, Baek shows how DongDong gradually achieves a better understanding of himself and others. Above all, this entails coming closer to his father and finding a pathway out of his solitary existence.

Another distinctive feature of Al-sa-taang is the way Baek integrates the book’s text, with its Korean characters, into the visual images, and indeed the plot. This technique also appears in her earlier books, but it truly comes into its own here, especially when conveying DongDong’s complicated relationship to his father, a man worn down by the everyday grind. The father’s endless harping fills a page with a suffocating block of text, while his unspoken affection for DongDong appears in light, twining words that float through the air first after the day’s chores are done. On a later page, Baek gives a similar voice to the falling autumn leaves. Lightly, floatingly, they bid a final farewell: goodbye, goodbye, goodbye. There is a poetic grandeur to the technique, with its suggestion that the world is a place both alive and ensouled.

The use of interior monologue to zoom in on an individual perspective is also a feature of Baek Heena’s most recent book, Na-neun ghe-dah (I Am a Dog), which forms a prequel to Al-sa-taang and is narrated by DongDong’s dog. It is a sensitive and finely-tuned portrayal of a dog and his human family where readers learn about how the dog sees the world, how he misses his mother, his friendship with the boy in the family, and his insight that his job is to take care of his human family. The emotional register is broad, the approach appealing and with the ring of truth. The story shows a respect for the needs and feelings of animals, as expressed in the unusually nuanced depiction of the dog, who goes through a variety of facial expressions, meaningful looks and body postures, and the acknowledgement of his capacity for longing, sorrow, and joy.

Baek Heena is an artist who is renewing the picture book medium through the bold and uncompromising development of new techniques and artistic solutions that inject elements from handcraft and animation into her books in new and exciting ways. Baek’s feeling for materials, spatiality, physical form, and gesture is impressive and innovative. Her intricately composed picture books invite multiple readings and close contemplation of their minutely constructed visual worlds. Yet their skillful execution never stands in the way of the story. Baek’s enchanting picture book worlds engage, amuse, amaze, and move us. The child’s perspective runs through them all, as does an unshakeable belief in the power of play and imagination in our lives. From the pages of her picture books a chorus of voices invite us to step into their world and find new ways to see, think, and feel.

I believe storytelling is necessary to view life more sweetly.

Acceptance Speech

"When I was little, I lived in my imagination world and liked to draw and played with dolls by myself all day long. And I still do the same thing. The only difference is I can end up with picture books after all playing."

The full Acceptance Speech

"I would be very happy to live in my stories"

Baek Heena’s nickname when she was little was “Pippi” because she adored Astrid Lindgren’s irrepressible heroine - and had freckles herself. The film-making process taught her how to tell a story in visual way, but the real reason she became a children's book maker was her desire to escape from the real world.

Read our interview with the 2020 LaureateBaek Heena in conversation with Jury member Elina Druker. Filmed at the 38th IBBY congress in Putrajaya, Malaysia, on 6 September, 2022.

Discover our laureates

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award is awarded to authors, illustrators and narrators, but also to people or organizations that work to promote reading.

Find out more about the laureates

Children have the right to great stories

To lose yourself in a story is to find yourself in the grip of an irresistible power. A power that provokes thought, unlocks language and allows the imagination to roam free. The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories.

Find out more about the award