“Books should be a fundamental human right”

The Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF) works in more than 400 First Nations Communities all over the Australian continent, promoting reading and literacy for First Nations children. We spoke to Ben Bowen, CEO of the ILF, about the importance of representation, the keys to the organisation’s success, and the significance of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award.

First of all, what does literacy mean for the ILF?

– We often talk about multimodes in literacy. Obviously, there’s the reading of texts and images, but there are also numerous other contexts involved in decoding texts. For us, it’s about integrating cultural understanding into literacy. By transforming stories from oral language into written form, children can draw upon their cultural knowledge and understanding of people and their surroundings to decode text.

How do you engage Indigenous Communities in fostering a love for reading and storytelling among the children?

– By engaging the entire Community. Even if the literacy of the people in the Community isn’t great, they can still interact and be part of the process. Building a sense of confidence and ownership is key for us. When the broader Community engages in a book, kids will naturally follow. Pick up a book anywhere in the world and start reading, and kids will flock to you!

– Sharing is an important thing in our Communities. We don’t see the kids reading to themselves, we see them piled up on top of each other, cuddling, sharing the stories. They’re all listening together, pointing at images, helping each other understand. It looks like chaos from the outside but to us it’s that beautiful Community experience.

Photo: Wayne Quilliam

Photo: Wayne Quilliam

Why is it important for kids to see themselves represented in the books that they read?

– When we first start reading, it’s really hard work. It’s not an enjoyable experience. To have a text with images that the children can relate to allows them to bring some of their own understandings into it. It helps them decode the text and go on a journey into something that they can explore themselves. If there’s a character in there that they can connect to, that speaks to them, that they can attach the voice of their parents or their auntie to, it helps them create that amazing experience of a theater in their minds.

Pick up a book anywhere in the world and start reading, and kids will flock to you!

What are the biggest challenges in your work?

– Definitely time and distance. Australia is a very big place – you can travel from Sydney to London more quickly than from Sydney to some parts of this country. To reach some of our Communities, you have to take planes, drive off-road, or take boats. We have to plan what materials we take carefully, because space on some of the light planes or boats is at a premium. There’s no shortage of great projects, there’s no shortage of people with brilliant ideas, but the ability for us to spend the time that we need with the Communities, that’s the challenge.

Through the Community Publishing program, ILF has published and distributed books in 31 languages. Can you tell a bit about the translation process?

– The whole translation process is led by the Communities. Sometimes it might be very much a word-for-word translation, sometimes it’s more of a syntax or sentence-based translation; it’s up to them to negotiate.

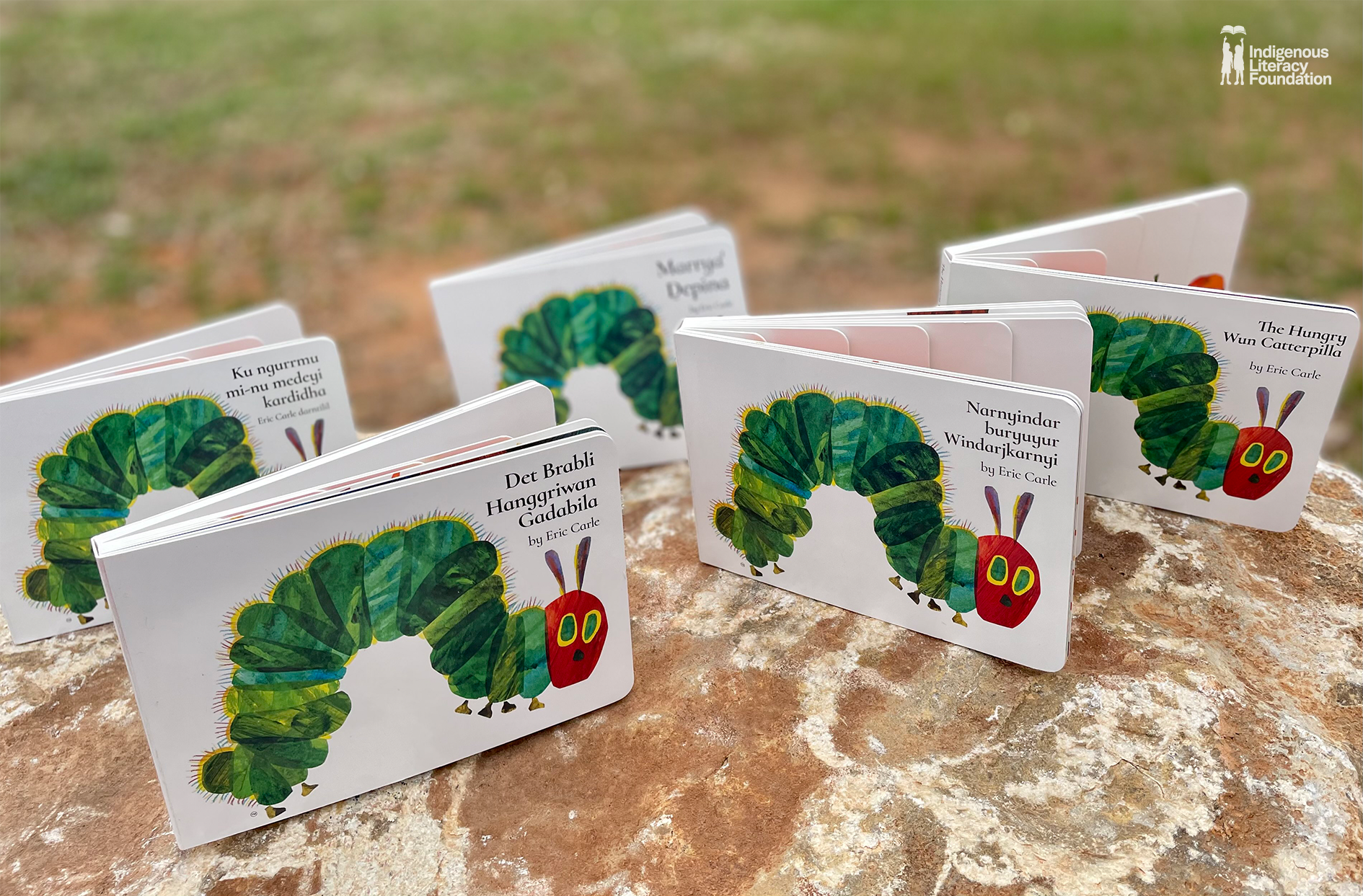

– It’s not always an easy process. An example is The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle, the first book that we translated into an Aboriginal language. One of the translations was held up for about 16 months because of the word 'lollipop', which didn’t exist in that language. But it’s important for us not to rush it, to give them time. This process is critical to the Communities, for their language to become living and moving into the future. It should be a fundamental human right, really, to have the opportunity to engage in books in your own language.

ILF has translated and published Eric Carle's book The Very Hungry Caterpillar in multiple First Nations languages. Photo: Wayne Quilliam

ILF has translated and published Eric Carle's book The Very Hungry Caterpillar in multiple First Nations languages. Photo: Wayne Quilliam

You’ve said that your aim is for remote Communities to drive ILF’s process. Why is this important, and in what way is ILF a Community led organisation?

– Community-led is core to us. Communities in Australia have been told for a long time what they should be doing, or what’s best for them. As Aboriginal people growing up in this country, we were not allowed to speak our own languages. Now, with the rapidly changing political space, Communities have gone from having to hide their identity to openly expressing it. This process has to be guided by the leadership group within Communities. Our role at ILF is to support these leaders and ask how we can be part of their journey.

How do you measure the effect of your work?

– About two years ago, we started a process of capturing comments and feedback from the Communities: if schools were using our books, what books the kids were choosing, what Communities were asking us for, if the packages we delivered actually had the books that they wanted or if there were some books that they didn’t want in the future. We have all that feedback coming back to us, and we now work with a consultant to bring all our data together. Another point is that the ILF is Community led, which means Community have a voice at all levels of the organisation and can direct us to provide better services.

– Another way of seeing the impact is through the personal stories we hear. I was on the Tiwi Islands last year, where I met a young boy who told me his mother had written a book for ILF a long time ago and that he, too, had a really great story for us. I tried to get more information from him, but he said he was not quite ready to tell the story yet. Later, I spoke with his mother. She had participated in our program ten years ago. She grew up with no books, and now she has a house full of books!

Photo: Wayne Quilliam

Photo: Wayne Quilliam

What do you think is the main key to ILF’s success?

– It’s definitely us being Community led. We can’t do any of the work we do without Community support. It’s really the greatest privilege – not only do they invite us into their homes and look after us while we are there, but they also give us the privilege of working with their stories. Sometimes these are highly personal, sometimes it’s a cultural story. They’re giving us that information and trusting us to bring it forward. That’s the big piece for us; it’s what makes us who we are.

What does the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award mean to you and how do you think it will affect your work?

– We really didn’t expect to receive this award, and I’m just blown away by the size of it. Of course in terms of money, but more importantly the integrity and the global presence that it has. This award is a new level of acknowledgement for the Communities that we’ve been working with for a long time. We can’t fully grasp what this will change – we’re just buzzing around, excited and hoping that everyone who’s been involved along the way understands that the lifetime of the ILF has come together in this award.

The translation process is critical to the Communities, for their language to become living and moving into the future.

Looking towards the future, what are your plans for ILF?

– A big thing for us at the moment is publishing. We have a small publishing team but a huge amount of interest from Communities. Unfortunately, there’s not that many jobs available in Communities. A lot of young people will leave their home and their family for opportunity elsewhere after they finish school. If we work with these young people, train them up and get them to work with publishing projects within Communities, then that can generate jobs and money. That’s what we’re really going to be focusing on in the upcoming years: on building that up to support Communities in telling their own stories and translating the books that they want.

Ben’s 5 tips for teachers and librarians working with multilingual kids:

- Allow them flexibility and ownership of their journey

- Recognize that the ability to tell stories is as important as being able to read them

- Encourage them to explore on their own and maintain a positive attitude about it

- Focus on what they’re getting right, rather than what they can’t do, and build momentum from there

- Acknowledge that there’s no shame in being a slow reader.

Highlights the value of all people’s own languages and stories

The Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF) encourages reading and promotes literacy by securing access to good literature for First Nations children of Australia. The organisation works in 427 First Nations Communities all over the Australian continent. ILF emphasizes the importance of First Nations children finding themselves, their culture and their languages reflected in the books they read.

Discover The Indigenous Literacy Foundation