From the eye level of the child

Marisol Misenta, widely known as Isol, is an Argentinian picture book artist, cartoonist, graphic artist, author, singer and composer. She debuted in 1997 and has been published in around twenty countries. Her style is expressive and at times explosive, using a sophisticated technique of double outlines and deliberate print misregistration where the lines and colours are not completely aligned.

Photo: Stefan Tell

Photo: Stefan TellQuick facts

The jury’s motivation

Isol creates picture books from the eye level of the child. Her pictures vibrate with energy and explosive emotions. With a restrained palette and ever-innovative pictorial solutions, she shifts ingrained perspectives and pushes the boundaries of the picturebook medium. Taking children’s clear view of the world as her starting point, she addresses their questions with forceful artistic expression and offers open answers. With liberating humour and levity, she also deals with the darker aspects of existence.

Isol is an illustrator, cartoonist, graphic artist, writer, singer and composer. She was born in 1972 and lives and works in Argentina.

Isol was born Marisol Misenta in Buenos Aires in 1972. She began her artistic education at the Escuela Nacional de Belles Artes, “Rogelio Yrurtia”, studying to be an art teacher, followed by a couple of years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires.

Isol is the writer and illustrator of about 10 published titles and has illustrated a similar number of published works by other authors. She made her debut in 1997 with Vida de perros, the story of a little boy who sees clear similarities between himself and his dog. Some of the characteristic features of Isol’s art were already present in this work: an expressive, sometimes explosive style with a muted colour palette, double outlines and deliberate misregistration in the colour printing of the motifs, where the lines and colours are not completely aligned.

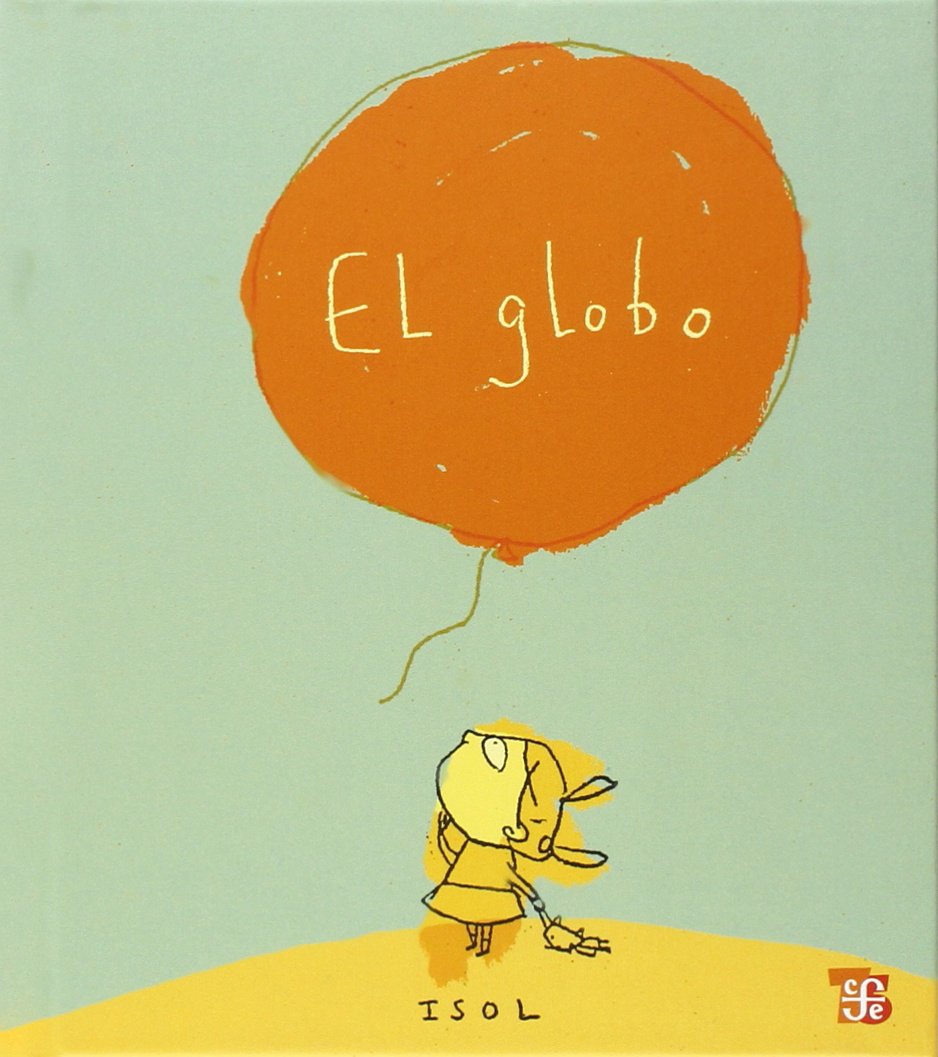

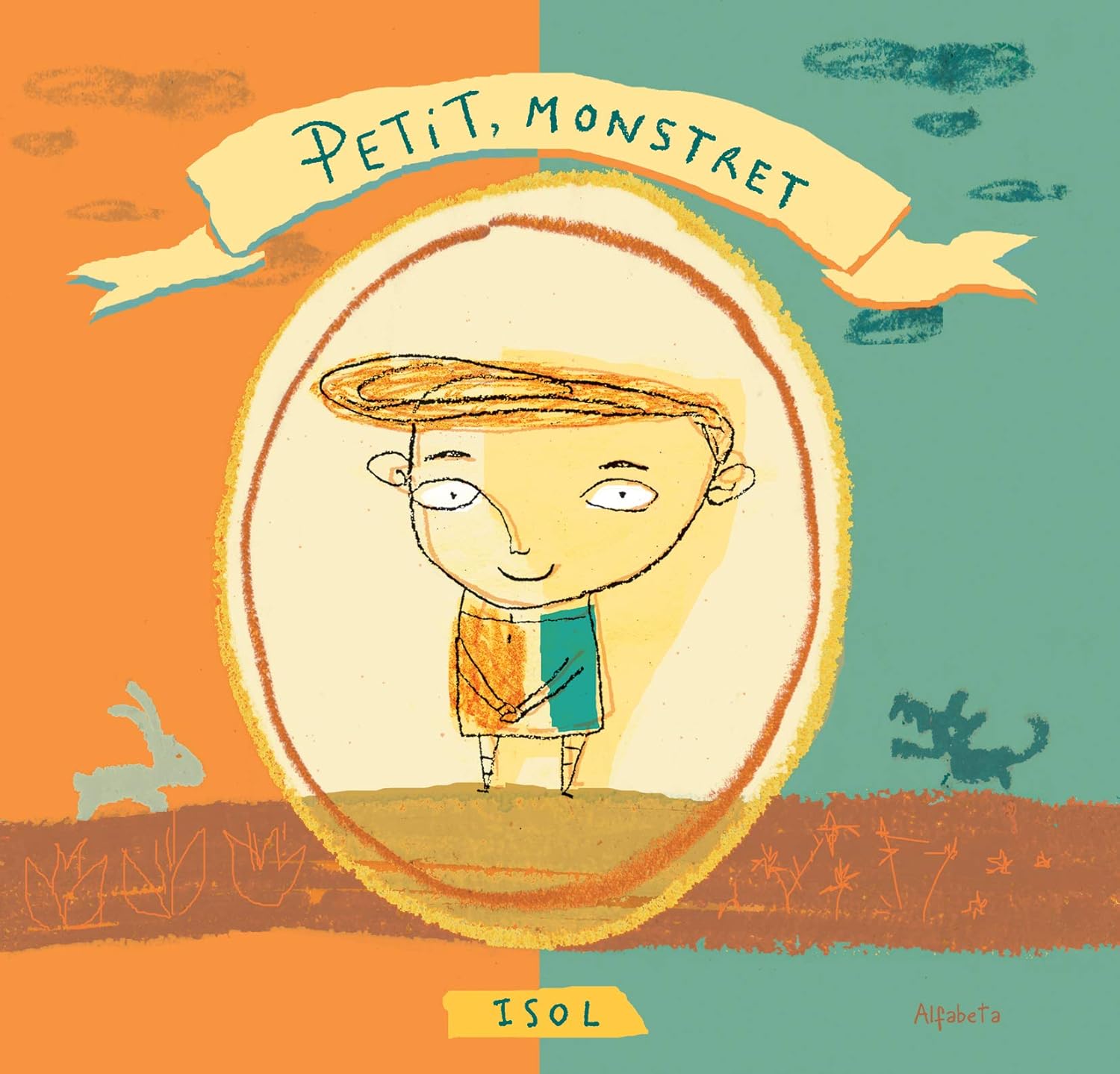

The stories are humorous with surprising twists, occasionally philosophical and always subtle. Isol is on the children’s side, seeing the world through their eyes and exposing the absurdities of the adult world. El Globo (2002) describes an angry, loud-mouthed mother who is transformed into a balloon. In Petit, el monstruo (2007), a child tries to figure out why his behaviour is considered praiseworthy on one occasion but cause for scolding on another.

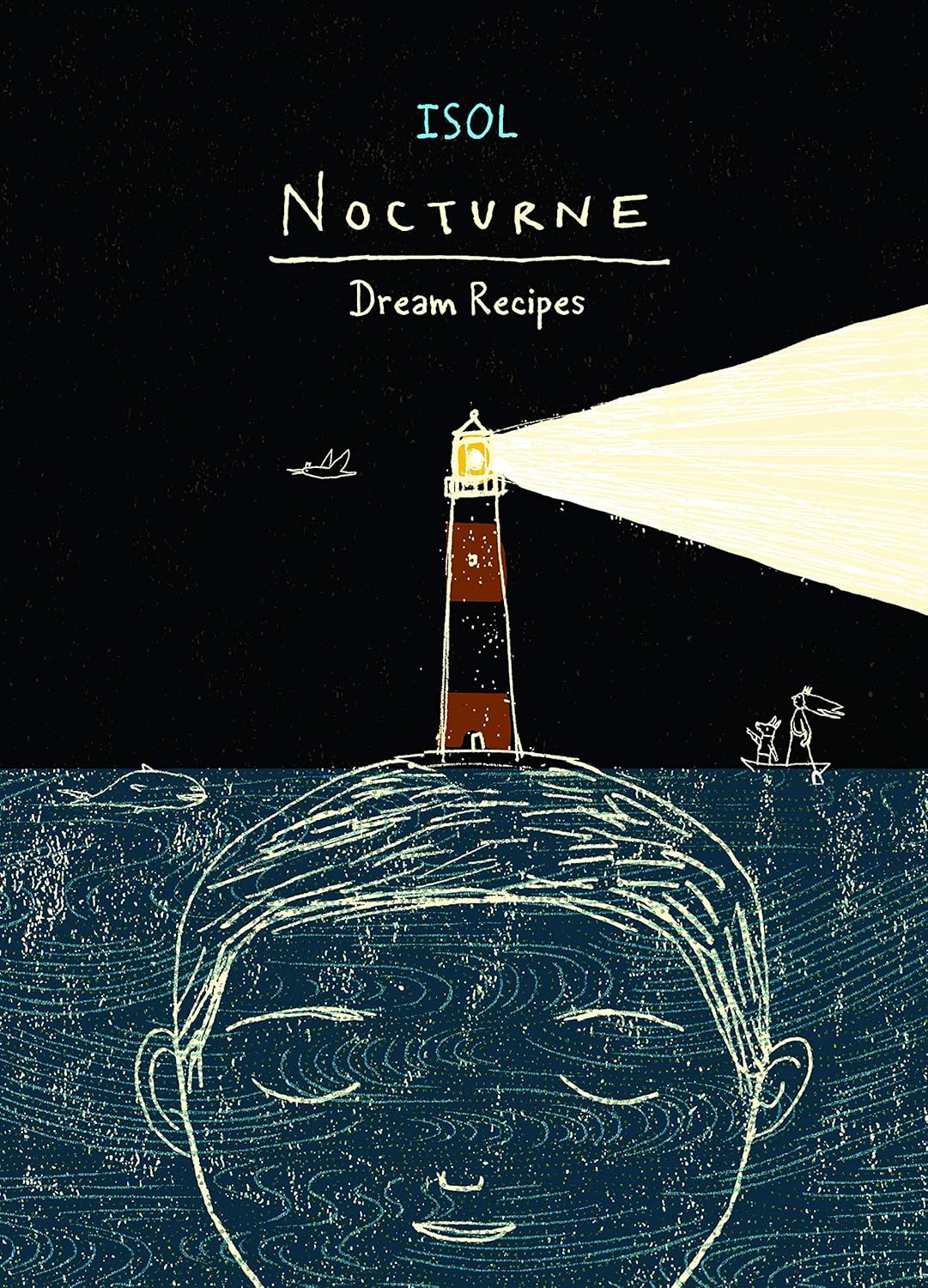

Isol is constantly exploring new formats and forms for the books themselves. Tener un patito es útil (2007) can be read from two directions with two different results: one story about what a boy can use a duck for, and another story showing what a duck can use a boy for. Nocturno (2011) is a beautiful introduction to the night’s dreams, printed in fluorescent colours that are best enjoyed in the dark. Isol’s great talent as a picturebook author is apparent in the overall experience created by the dramatic composition, the choice of colours and the intensity of the drawn line.

Her long-standing collaboration with Argentinian poet Jorge Luján has produced a large number of books where Isol, through her illustrations, is the story’s co-author rather than an illustrator in the conventional sense. Her works have been published in some 20 countries.

Open narratives with room for multiple interpretations

This text was written in 2013 by members of the award jury.

Isol from Argentina is an illustrator, cartoonist, painter, graphic artist, poet, singer and composer. Born Marisol Misenta in 1972, she grew up in an academic family in Buenos Aires, where she still lives with her husband and one-year-old son. According to her own account of her childhood, she was constantly reading and writing, always surrounded by the best books and the artistic, avant-garde Argentinian comic books of the time. Her grandfather wrote comic book scripts, while her brother Federico devoted himself to music.

Isol began her artistic education at the Escuela Nacional de Belles Artes, “Rogelio Yrurtia”, studying to be an art teacher, followed by a couple of years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires. She gradually started introducing textual components to her paintings – epigraphs, inscriptions or mottoes, as she calls them – and came to realize that she needed to find a way to connect her writing with what she was trying to accomplish in her pictorial art. Her interest in telling stories through pictures stood her in good stead when she started working as a newspaper cartoonist, a job that requires the ability to capture an event in a single image.

In 1996, Isol entered the manuscript of her first picturebook, Vida de perros, in a picturebook competition in Mexico. One of the jury members replied by fax, saying that unfortunately she could not be a winner because her images were too “eccentric”. However, the jury member in question was Daniel Goldin, the publisher at Fondo de Cultura Económica, a major publishing house. He had fallen in love with the book and promised Isol he would publish it if she would modify her images a little. “The eyes were too psychotic, for sure, and they asked me to tone down the smiles,” she later explained.

Isol found herself unable to change anything, but instead wrote a five-page theoretical justification. The book received an honourable mention in the competition and was published largely unchanged. Many aspects of her art that she would go on to develop were already present in this debut work.

Vida de perros was the beginning of a long-term working relationship with the publishing house, Fondo de Cultura Económica. As a result, most of Isol’s books have been published in Mexico, 11 hours away from Buenos Aires by plane, rather than in her home country. Following her debut, she published several more picturebooks in fairly quick succession, employing the same expressive style.

As a visual storyteller, Isol sees things from the eye level of a child. She is unfailingly loyal to her young readers. A straight, consistent line of energy and trust runs through all her works. This energy is occasionally explosive, always expressive, never latent. Isol trusts in children’s ability to meet her in the story. As an artist, she moves freely across the boundaries between pictorial art, music, design and poetry, and this too resonates in her books.

Isol’s works contain extreme elements, fun elements and unpredictable elements, along with humour and an ability to create visual narratives with a surprising twist.

In the mildly absurd El Globo (2002), the angry, loud-mouthed mother is transformed into a balloon that her daughter can hold on a string while out for a walk. She meets another girl who is out with her mother. “What a lovely balloon!” says the other girl. “Yes, and what a lovely mummy!” replies the daughter. When they part, they each think, “Oh well, you can’t have everything!”

This story was controversial, Isol admits, but has multiple interpretations, one of which is as a story of liberation. The same can be said of the boy Petit in Petit, el monstruo (2007), who cannot figure out the dichotomies of adult life. How can people like you and think you are nice one moment, and then the next moment scold you for doing more or less the same thing? Here, Isol uses a sophisticated technique of double outlines and shadows to underline the ambivalence.

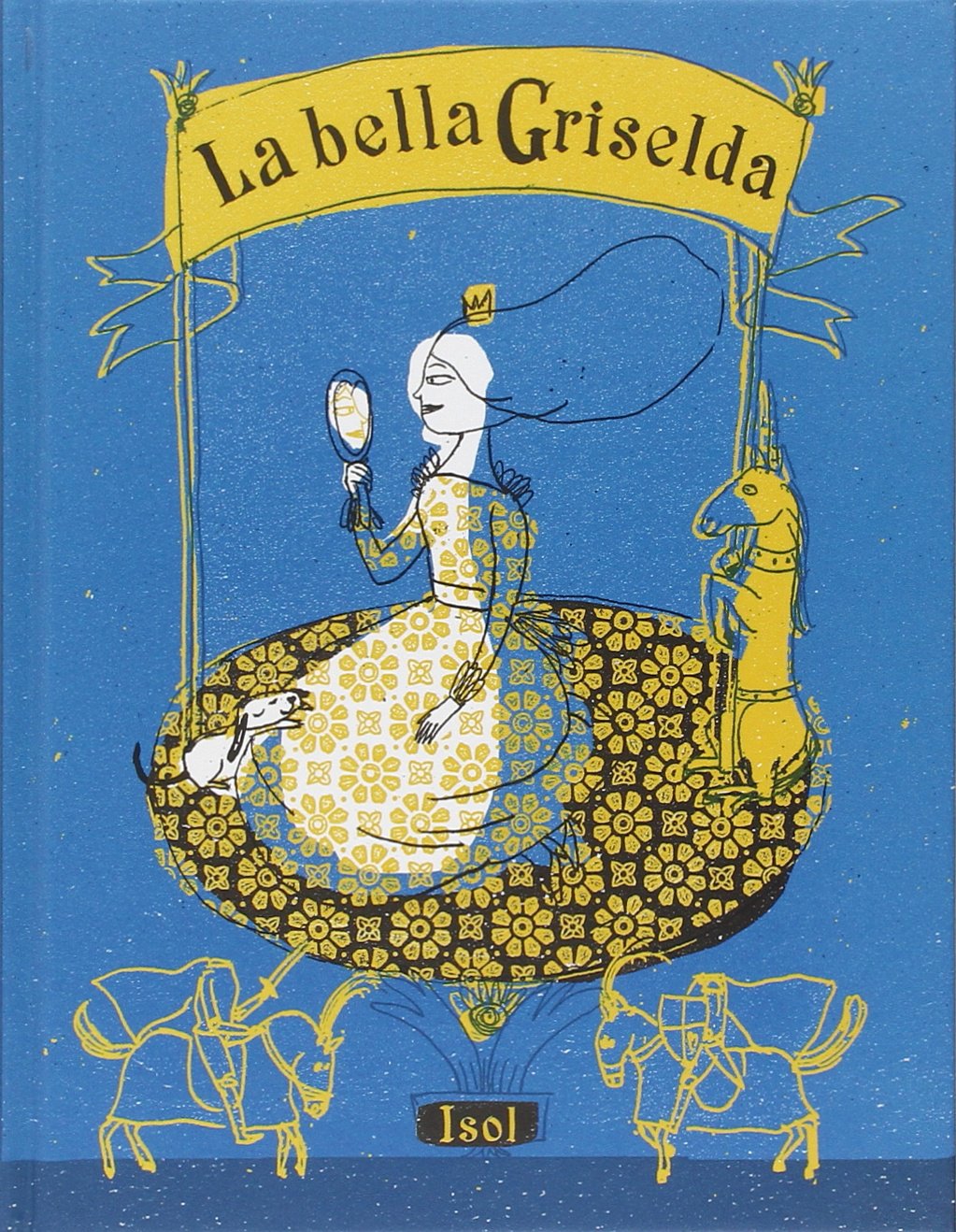

Maternal relationships and family secrets are a recurring theme throughout Isol’s works, as in Secreto de familia (2003), where a child discovers that even her friends and classmates try to conceal what their mothers get up to at home when no-one is watching. Fatal beauty is the theme of La bella Griselda (2010), a cruel but humorous tale about a series of suitors who literally lose their heads in front of the beautiful princess Griselda. One day, she suffers the same fate herself in front of her own daughter, an equally beautiful little princess.

The Argentinian poet Jorge Luján, living in Mexico, suggested early on in Isol’s career that she should draw comic strips based on his scripts. The result was an exquisite series, Equis y Zeta, the first volume of which appeared in 2000. This was where Isol discovered the thin, nervous, slightly broken line, the muted colour palette and the pared-down style, which she went on to develop both in subsequent works co-authored with Luján and in her own picturebooks. This style is frequently characterized by double outlines and deliberate print misregistration, where the lines and colours are not completely aligned. Isol sets out to reproduce this common phenomenon in graphic art, since it reminds her of the old picturebooks her grandmother gave her as a child: “They were often worn and sun-bleached. I like to start with a yellow, sun-bleached colour, to create a similar timeless quality, and then add one or two clearer colours as a kind of accent,” she explains.

Isol often emphasizes the importance of technique to the overall experience of a book, pointing out that it has narrative qualities in itself. Her aesthetic is as easy to recognize as it is hard to define, as she herself says. It is based on layers of conscious choices, in which drawing is a powerful tool able to express something that cannot be articulated in any other way. This personal expression conveys a sense of something handmade, be it graphic expression or, as in Pantuflas de perrito (2009), using a ballpoint pen and allowing the paper fibres and dirt to become part of the expression.

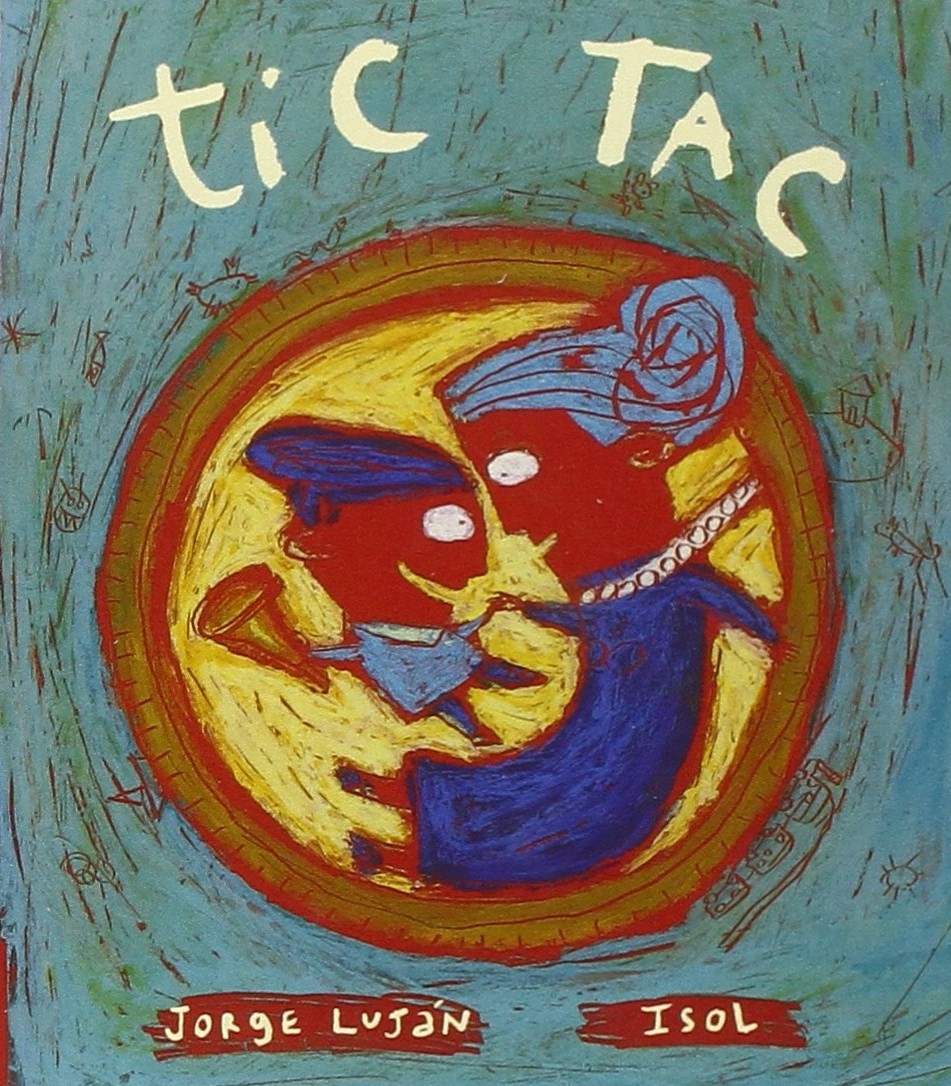

In colour terms, Tic Tac (2002), Isol’s first picturebook co-authored with the poet Jorge Luján, marks a departure from her usual palette. In Luján’s poem, a small boy wants to know how much his mother loves him. “In this case I almost turned into a Fauvist,” says Isol. In an interview many years later, she referred to “the red colour, so shiny, that draws the outline and makes other colours vibrate. […] I intend the outline to be almost always the soloist voice in the drawing, the main source of expression in the picture, and I want colours to accompany this idea.” Isol received the Golden Apple award for Tic Tac in Bratislava in 2003.

A unique ability to change and broaden her perspective, in terms of both aesthetic and content, is what sets Isol apart. In her larger works co-authored with Jorge Luján, Mi cuerpo y yo and Ser y Parecer (2005), she tackles complex scenarios involving psychological and philosophical issues in a bold, playful and visionary way. Here, everything happens in the brief but highly charged texts: “They gave me the wings to create books that are artworks in their own right, as it were, since the story did not need to be told in pictures but instead made me feel like a poet myself.”

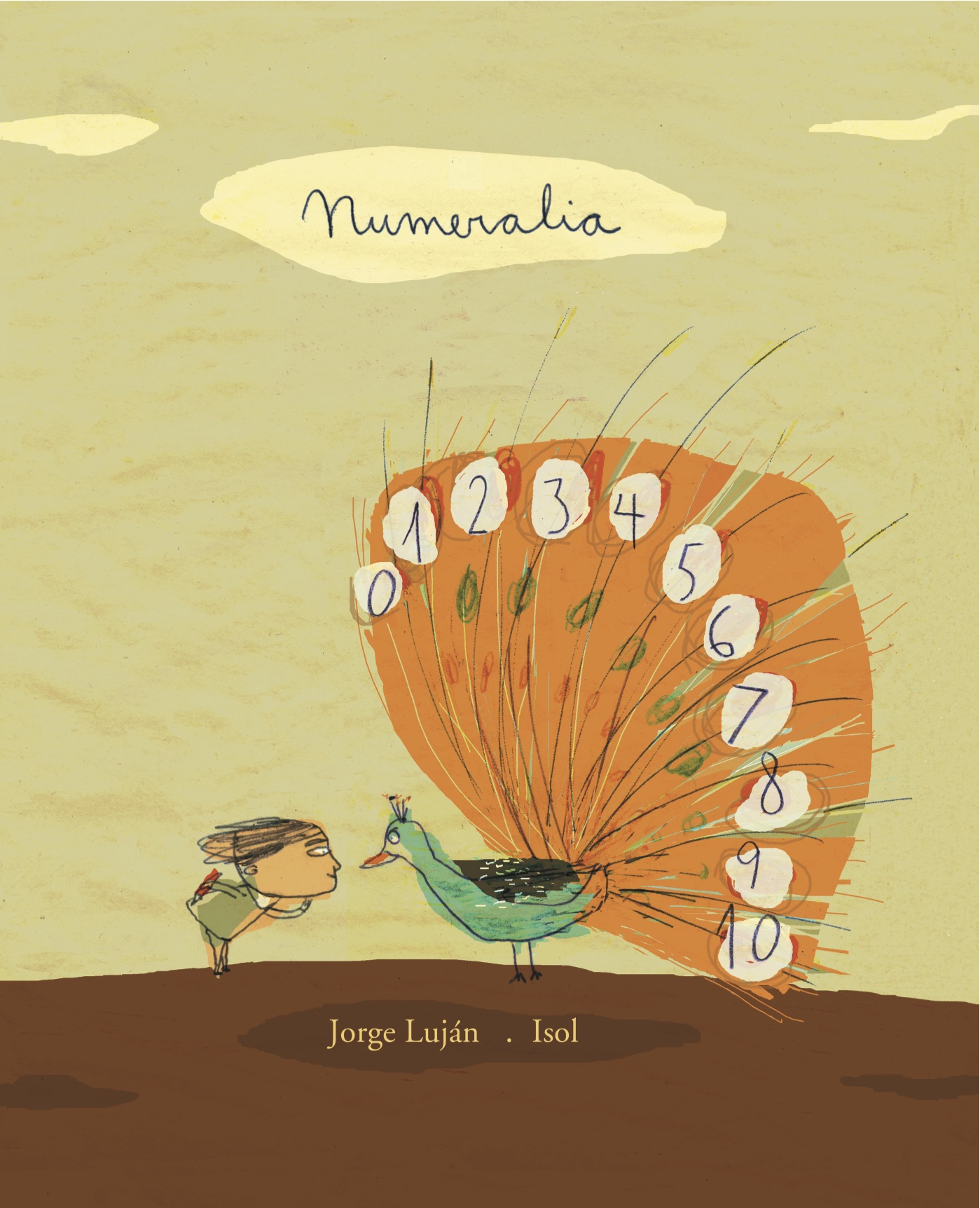

Other products of Isol’s collaboration with Luján include Numeralia (2007), which offers a kaleidoscope of visual and intellectual possibilities arising from an apparently simple theme – presenting the numbers one to ten – and Pantuflas de perrito, based on poems about children longing for a pet to cuddle with. The text of the latter book is the result of online collaboration with children in Mexico and Argentina.

Among Isol’s best-known works is her illustrated version of El cuento de Auggie Wren (2003) by Paul Auster, in which she builds up scenes using a three-dimensional collage of drawings, objects and photographs in a highly suggestive, theatrical style. “In this case, it was a finished text that already conveyed all the psychological details, so I was free to let the images follow other narrative lines,” Isol explains.

Isol’s pictorial narratives do not minimize problems or paint an idealized picture of reality. They can be extreme and shocking, but they give readers the insight and courage to think bold thoughts of their own. Isol creates open narratives with room for multiple interpretations. Each story requires its own staging, and therefore the style frequently changes from one book to the next, according to Isol. There is an ostensible simplicity to her working method, especially in the forming of the characters. Her great talent as a picturebook author is apparent in the overall experience created by the dramatic composition, the way we are led into the narrative, the choice of colours, the recurring double outlines, the intensity of the drawn line and its interaction with either coloured surfaces or the white paper.

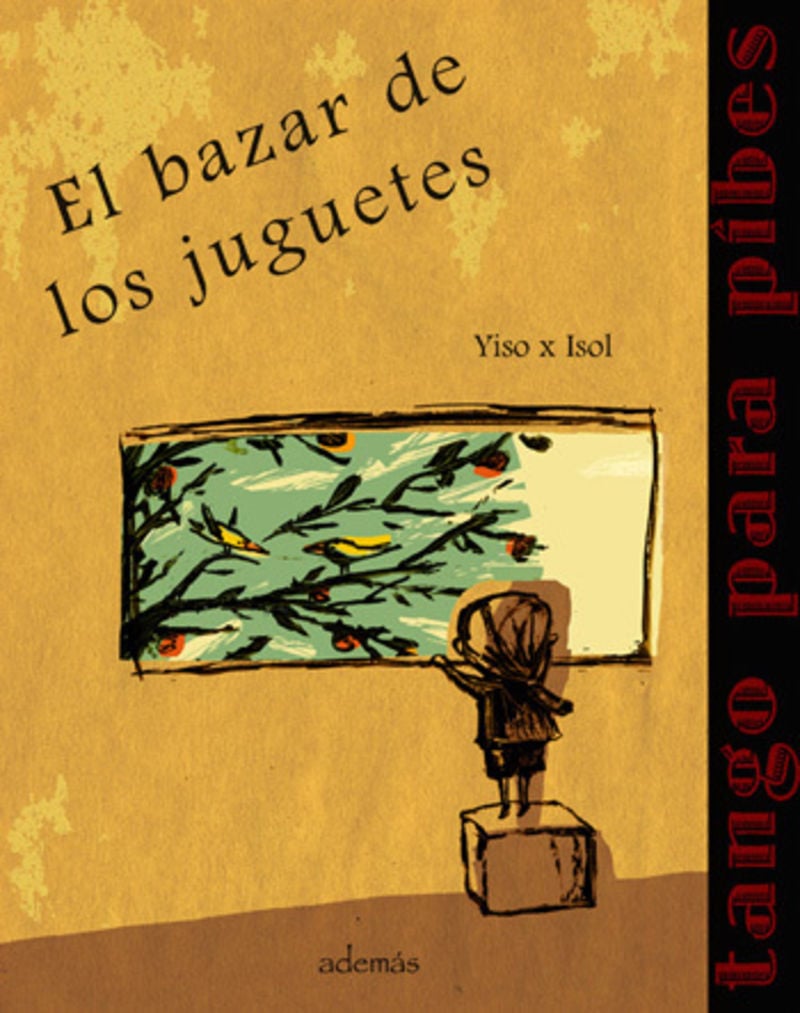

Isol was involved in a project of a different kind where several artists each described an Argentinian tango to children in book form. She chose to illustrate a tango by Reginaldo Yiso. The result was El bazar de los juguetes (2009), a beautiful and slightly enigmatic picturebook about wish fulfilment and secret dreams.

Isol’s creative drive also leads her to explore new formats for the books themselves. One example is Tener un patito es útil (2007), a book for young children in a surprising, “double-narrated”, fold-out form that switches the narrator’s perspective. One of her most recent works, Nocturno (2011), is printed in fluorescent colours so that it can be read in bed in the dark, as an introduction to the night’s dreams.

Asked why she creates picturebooks for children – which she is not certain that she does – Isol replies: “I’m a grown-up, and I happen to like them. I like the fact that they encrypt no lesson, that they are not closed in form or meaning, that text and image establish a dialogue which at times may be paradoxical or slanting. Not only mine: I love all good illustrated books, I have consumed them all my life. I hate it being said ‘it’s for children’ when something is bad. It gets on my nerves. Working with childhood, evoking it, is something absolutely powerful.”

Isol is now considered Latin America’s foremost author of picturebooks. Her 20-odd works have been published in almost as many countries. Besides being a successful illustrator, she sings in the electronic pop duo Isol/Zypce alongside her brother Federico and in a baroque ensemble called The Excuse. She also recorded a CD with the American band Alsace Lorraine (Dark One, 2007). Between 2000 and 2005 she made a handful of recordings with the Argentinian band Entre Rios.

Sources:

Mariana Enriquez, “El imperio de Isol”, Radar, November 28, 2010

Claudio Martyniuk, “Es bueno que los libros infantiles sean incómodos porque así se crece”, Clarín, November 21, 2010

Isol, “Digital natives are readers too: The new generations of readers”, International Book World Congress, Fondo de Cultura Económica, September 2009, Mexico City

Javier Sobrino, interview with Isol, Peonza Magazine, March 2008

Roberto Soleto, interview with Isol, Imaginaria, 2005:154

María Emilia López, “Ilustracioón, Transgresión y Rupturas”, Punto de Partida, 2005:11

Discover our laureates

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award is awarded to authors, illustrators and narrators, but also to people or organizations that work to promote reading.

Find out more about the laureates

Children have the right to great stories

To lose yourself in a story is to find yourself in the grip of an irresistible power. A power that provokes thought, unlocks language and allows the imagination to roam free. The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories.

Find out more about the award