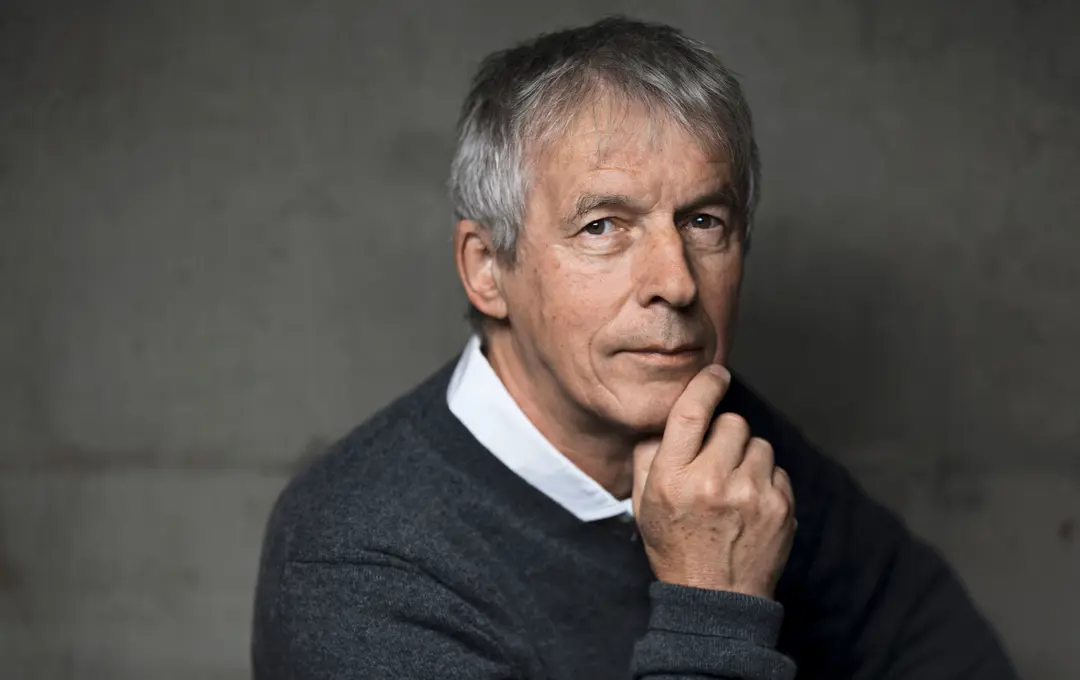

A brilliant renewer of fairy tale traditions

Jean-Claude Mourlevat is one of France’s leading children and young adult authors. With a particular love for fairy tale, fable and fantasy, he draws on literary traditions to create worlds that resemble no other. Since his publishing debut in 1997, his books have been translated into nearly 30 languages.

Quick facts

The jury’s motivation

Jean-Claude Mourlevat is a brilliant renewer of fairy tale traditions, open to both hardship and beauty. Time and space are suspended in his fictional worlds, and eternal themes of love and longing, vulnerability and war are portrayed in precise and dreamlike prose. Mourlevat’s ever-surprising work pins the fabric of ancient epic onto a contemporary reality.

Jean-Claude Mourlevat began his working life as a German teacher before changing paths and working as an actor, clown and director. It was the theater that led him to begin writing, and in 1997 he made his authorial debut with the picture book Histoire de l’enfant et de l’oeuf.

Jean-Claude Mourlevat’s writing is wide-ranging and diverse. He writes novels of social critique, but has a particular fondness for the fairy tale, fable and fantasy genres. He surprises readers with each new book, assuming new guises and using unexpected narrative devices. References to classic works, metaphor and simile link his stories to the present day.

A love of books and literature flows through all his writing. This may be because he spent his childhood in a home with almost no books. Jean-Claude Mourlevat grew up on a farm as the fifth of six siblings. He spent eight years at a boarding school where the rules were harsh, the teachers strict and he felt constantly homesick and unhappy. He has said in interviews that literature became his salvation.

The phone call

A profound and life-affirming humanism

This text was written in 2021 by Boel Westin and Lena Kåreland.

A love for books and literature flows through the work of the French author Jean-Claude Mourlevat. Since his publishing debut in 1997, he has authored more than thirty books that have been translated into nearly thirty languages. Drawing inspiration from literary tradition, he creates worlds that are utterly his own, unfolding stories filled with unexpected turns and unforeseen resolutions.

The irresistible animal story Jefferson (2018) tells the story of a hedgehog who loves to read. He is a library regular and his favorite book is an adventure novel entitled “Seul sur le fleuve”—a tale so thrilling and so moving that it keeps him up two nights running and has him pulling out his handkerchief on multiple occasions. When the little hedgehog is accused of murdering his hairdresser and forced to flee from the safety of his home, his novel-reading habit proves to be of critical importance.

Le petit royaume (2000) is a picture book set in a wintry northern kingdom. In this land, the king has built a library that is more beautiful than the palace itself. He and his people sink delightedly into their reading. When complaints arise about the state of the roads, the king has the carriages filled with books and encyclopedias. But everything changes when a new king takes the throne. He bans books completely and builds up the country’s defenses with armies and warships. Eventually we learn that the warrior king is illiterate. When he finally learns to read and write, his disposition changes instantly, and he too begins to devote all his time to reading. Thus, the importance of literature and the arts are effectively contrasted with dictatorship and war in a manner that even young readers will understand.

The wide-ranging novel Le chagrin du roi mort (2009) features a grand library filled with thousands of volumes and redolent with the good smells of leather, wood, and paper. Carts carry visitors around the stacks to find the boo ks they are looking for. The centrality of books and reading in Mourlevat’s writing is perhaps explained by the fact that he spent his own childhood in a home without books. He was born in 1952 in Ambert in Auvergne as the fifth of six siblings. His family lived on a farm and his father was both a farmer and a miller. He has said that the countryside of his youth made a strong impression on him: the dark nights and deep forests, the snowfalls and the spring thaws.

The autobiographical Je voudrais rentrer à la maison (2002) is a dark memoir in episodic form about the eight years that Mourlevat spent at boarding school, from the age of ten until his graduation. The school rules were harsh, the teachers were strict, and the young Jean-Claude was constantly homesick and unhappy. More than once, he has said that literature became his salvation. His first important reading experience was Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, a book that affected him deeply. The experience of reading its opening line—“I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York”—was like hearing a voice coming from the pages, speaking directly to him. Also of foundational importance was Franz Kafka’s The Castle, which Mourlevat has called the book of his life.

Late debut

Jean-Claude Mourlevat made his authorial debut relatively late, in 1997, with the picture book Histoire de l’enfant et de l’oeuf. Since then, he has worked as a writer full-time. Before turning to writing, he trained to be a teacher, studied German in Strasbourg, Toulouse, Bonn, and Paris, and spent five years in the teaching profession. He has also studied theater, worked as a director and actor, and performed as a clown. He has staged works by such classic playwrights as Brecht, Cocteau, and Shakespeare and has also written his own plays. According to Mourlevat, theater work and writing have much in common. Both jobs involve arranging and organizing, and both are simultaneously technical and emotional, a mixture of keeping control and daring to let go.

One of Mourlevat’s more theatrical novels is L’Enfant océan (1999, The Pull of the Ocean), a book that garnered considerable acclaim and introduced Mourlevat to a wider audience. It is a multi-stranded story where multiple narrative voices rise and fall in counterpoint with one another. In a series of episodes, like dramatic acts, we follow seven siblings, three twins and their younger brother, as they flee from a threatening home environment. Yann, the youngest, is ten, but he is physically no larger than a two-year-old and he has almost no oral language. Yet he is gifted, loves to read, and has magic powers. And so it is he who leads the children on their difficult and dangerous way westward toward the sea; he who becomes a guardian angel for his older siblings. Yann is just one of many characters in Mourlevat’s books who belong not to the real world but to the world of magic and fairy tale.

The events that transpire in L’Enfant océan are recounted by the siblings and their parents as well as by the people the siblings meet on their journey—some of whom merely stand back and watch, and others of whom actively intervene to help, like the driver who offers them a lift or the baker who gives them bread. The prose adapts flexibly and rhythmically to the shifting narrative voices, becoming a mirror of the narrators’ different personalities. L’Enfant océan also exemplifies the way Mourlevat borrows from fairy tales and their tellings: in this case, the story of Tom Thumb as told by the French author Charles Perrault in his fairy tale collection from 1697. While the fairy tale theme gives Mourlevat’s narrative a timeless quality, an acid realism also anchors the narrative in modern-day France. Using small means, Mourlevat vividly captures the misery and violence of the siblings’ daily life with their abusive father. He also effectively illuminates social hierarchies: for example, in a scene where the school social worker visits the siblings’ home and speaks briefly with their mother on the steps, but is not allowed inside.

An eminent epicist

Mourlevat’s richly diverse work addresses itself not only to young children and teens but also to adults. He writes novels of social critique, but works mainly in the world of fairy tale, fable, fantasy, and science fiction, and he has also written autobiographical and documentary works. In the latter category is Sophie Scholl: Non à la lâcheté (2013), a book about the German student activist who resisted the Nazi regime and was captured and executed by guillotine at the age of twenty-two.

But above all, Jean-Claude Mourlevat is an epicist of the first rank. He creates imaginary worlds that are utterly his own, drawing on venerable literary traditions to create new stories full of surprises, unexpected turns, and unforeseen resolutions. He erases genre boundaries while always preserving a connection to a contemporary world that we see, through his eyes, in a fresh new light. The classic fairy tale conflict between dark and light is an important element in Mourlevat’s novels, but his battles tend to develop in unexpected ways and have unpredictable endings—as in Le chagrin du roi mort, where two brothers are separated and then pitted against one another. Courage, self-sacrifice, and solidarity are all put to the test in confrontations with evil, barbarism, and war.

Mourlevat’s stories also reward thematic analysis. Writing down the things we experience on paper can be both a way to fight forgetting and a step in forging an identity, as it is for the character Tomek in La rivière à l’envers (2000). This is a story in two parts told by two narrators: Tomek and Hannah, both of whom are searching for a river that flows backwards, whose life-giving waters can prevent death. The same story is thus told from different perspectives. As readers, we are treated to a picaresque tale that winds through strange milieux of an allegorical and mythical nature: the forest of forgetfulness, the island that does not exist, the sacred mountain. Hannah makes her way through vast desert landscapes of rolling dunes, glimpsing nothing but a lone camel herder here and there in the distance, to save the bird who means so much to her. Here, the age-old theme of the water of life is rendered with rare sparkle and individuality.

A fondness for winter and snow

Mourlevat’s stories are often set in environments where both place and time are uncertain. At times, we seem to be in a medieval world, centuries before industrialization and modern digital society: a world without modern transport, such as cars, trains, and planes; a world without computers or cell phones. We recognize the symbolic settings of the fairy tale—the forest, the mountains, the sea—but Mourlevat fills in their usually vague outlines with realistic details. Often, he conjures up desolate winter landscapes of penetrating cold, mountains of snow, and biting winds, as in the dramatic narrative Le chagrin du roi mort (2009). Here, his images of winter have a Nordic feel, and the tale of the dead king’s sorrow has many points of overlap with Njál’s Saga, the most famous of the Icelandic sagas.

Other stories, in contrast, are clearly anchored in time and space. That is true of La Balafre (1998), Mourlevat’s first young adult novel. Here, the setting is a French village. The thirteen-year-old Olivier and his family have moved to the village for his father’s job. Olivier feels abandoned and is left to spend much of his time alone. The story oscillates between fantasy and reality as bit by bit, Olivier is drawn into a shadow world where mystical events occur. He is attacked by a dog that no one else can see, and he comes into contact with an older woman. Gradually, a history unspools that goes back to the German occupation in the early years of World War II: a story of informants, racism, and Jewish persecution, but of resistance as well.

Also set in the present day is the remarkable novel Terrienne (2011), a highly original work of science fiction. Its seventeen-year-old protagonist, Anne Collodi, is searching for her older sister, who got married and then disappeared without a trace. In part, the novel can be seen as a retelling of Bluebeard, the horrifying tale of a man who kills his wives and keeps their corpses locked in a secret room. Anne’s sister has been abducted by her husband to a parallel world: a frightening place devoid of life, movement, laughter, and joy. Life in this world is efficient, silent, structured, and prescribed in every detail. Oxygen itself has been abolished and the people have been forbidden to breathe. For dissenters, penalties include being thrown out of a window. People tend to die by age fifty, often of boredom. This infinitely fascinating and surprising story can also be read as a creative paraphrase of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It celebrates the physicality of life, including plain ordinary life with all its smells, sounds, visual impressions, dirt, and noise. It is no accident that Anne shares her last name with the author of the classic tale of Pinocchio, the wooden puppet who longs to be alive.

The symbolic journey

Mourlevat’s characters are often abandoned, parentless and vulnerable. They must forge a future for themselves. The journey or pilgrimage is therefore a common feature of his stories, and usually carries a symbolic meaning. A young person’s journey might be one of initiation, a passage into adult life. Setting off on a journey may also express a temporary cutting of ties with the adult world. In La rivière à l’envers, Tomek rejects the ennui of his everyday life and the future that has been charted for him in order to explore unknown territories and take on difficult challenges. In Le chagrin du roi mort, it takes seven years for one of the brothers to return home from war. During this time, he wanders aimlessly in the vain hope of finding his beloved, from whom he was separated during the war. The journey, it would seem, represents a necessary break from reality, part of a maturation process in which a young person is forced partly into isolation, partly into a wrestling match with existential questions. And in Mourlevat’s books, where young people face merciless reality, suffering, separation, and death, a happy or harmonious ending is never guaranteed.

School, especially boarding school, is a setting to which Jean-Claude Mourlevat has frequently returned. Usually, he portrays schools as almost prison-like institutions. So it is in the award-winning Le combat d’hiver (2000, Winter Song), a young adult novel that has been translated into twenty languages. At the center of the story are four parentless teenagers, two boys and two girls, who attend a boarding school with extremely punitive and repressive rules. They run away from the school to take up their parents’ fight against tyranny and cruelty in a dictatorial society. It is a skillfully constructed story that unfolds partly in a fantasy world. Mourlevat works with contrast, paints in black and white, pits good against evil, and sends bloodthirsty dog-people slavering across his pages in an evocation of the gladiatorial games of ancient Rome. Yet more than anything, the story is an impressive tribute to freedom and art.

Humanism

More humorous is the depiction of the school in La troisième vengeance de Robert Poutifard (2004), a Dahlesque tale of a teacher who has always hated his job and his troublesome students. When he retires, he decides to exact revenge for all the humiliations he has suffered over the years. His revenge campaign is described with wit and extremely dark humor in this brutal look at teaching conditions. A more easygoing brand of humor is on display in La ballade de Cornebique (2004). This book, like Jefferson, is set in the animal world. Cornebique is a little goat who has been unlucky in love. He sets out on a journey to get some perspective and ends up staying away for five whole years. Cornebique’s experiences and adventures, both happy and sad, are recounted in language by turns burlesque and exuberant, by turns mournful and melancholy.

In Jean-Claude Mourlevat’s fictional worlds, music and art form powerful counterpoles to the brutality and barbarism of the world. In Le combat d’hiver, Milena’s song inspires new hope and solidarity in the hearts of the people who have gathered around her. And for Cornebique, who is a virtuoso on the banjo, music is a source of both comfort and joy. Mourlevat’s work displays a profound and life-affirming humanism, often made manifest in the actions of his characters. His books express an exceptional longing for goodness that makes his stories truly affecting. Time and space hang suspended in his literary universe, a space he makes big enough for both the hardest and the most beautiful parts of our lives.

The land where this story begins is inhabited by animals who can walk on their hind legs, talk, borrow books from the library, fall in love, send text messages and go to the hairdresser's. The neighboring country is home to humans, who are the most intelligent of animals.

"Writing comforts me"

How does Jean-Claude Mourlevat choose the subjects for his books? Where does he write and how did he develop his powers of imagination?

Read our interview with the 2021 Laureate

Acceptance speech

"I feel proud and happy, of course, but at the same time I feel like hiding in a hole, deep in the forest, like a hobbit, or like Jefferson, my little hedgehog. Because it’s so moving, so overwhelming. I feel flabbergasted."

The full Acceptance SpeechJean-Claude Mourlevat in conversation with Mårten Sandén at Litteralund (2024)

Discover our laureates

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award is awarded to authors, illustrators and narrators, but also to people or organizations that work to promote reading.

Find out more about the laureates

Children have the right to great stories

To lose yourself in a story is to find yourself in the grip of an irresistible power. A power that provokes thought, unlocks language and allows the imagination to roam free. The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories.

Find out more about the award