A darkly radiant realism

Laurie Halse Anderson is one of America’s foremost writers for young adults. Her breakthrough novel, Speak, was published in 1999 and has been translated into many languages and adapted for film. In her richly expressive novels for young people she gives voice to the adolescent experience with sometimes brutal honesty. The yearning for love and belonging is a recurring theme for Anderson.

Photo: Susanne Kronholm

Photo: Susanne KronholmQuick facts

The jury’s motivation

In her tightly written novels for young adults, Laurie Halse Anderson gives voice to the search for meaning, identity, and truth, both in the present and the past. Her darkly radiant realism reveals the vital role of time and memory in young people’s lives. Pain and anxiety, yearning and love, class and sex are investigated with stylistic precision and dispassionate wit. With tender intensity, Laurie Halse Anderson evokes moods and emotions, and never shies from even the hardest things.

Laurie Halse Anderson (b. 1961 in Potsdam, New York) debuted as an author in 1996. In her richly expressive novels for young people—all narrated in the first person—Anderson gives voice to the adolescent experience with sometimes brutal honesty. Here is resignation, even desperation, but also a determination for change kept alive by the search for meaning, identity, and truth. The yearning for love and belonging is a recurring theme for Anderson.

Laurie Halse Anderson makes her home in Philadelphia. Alongside her writing, she is powerfully committed to issues related to sexual violence, diversity, and book censorship.

The award ceremony was held on Tuesday, 2 May, at Konserthuset in Stockholm. The award diploma was presented by HRH Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden.

The phone call from the Jury

The yearning for love and belonging

This text was written in 2023 by Boel Westin and Elina Druker.

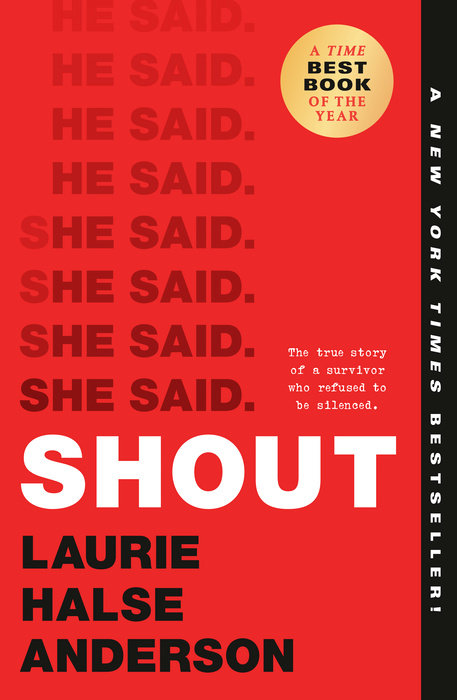

A survivor who refuses to be silenced. That is how Laurie Halse Anderson describes herself in her poetic memoir Shout (2019), and it is true for many of her main characters as well. In her richly expressive novels for young people—all narrated in the first person—Anderson gives voice to the adolescent experience with sometimes brutal honesty. Here is resignation, even desperation, but also a determination for change kept alive by the search for meaning, identity, and truth.

Laurie Halse Anderson, who published her debut novel in 1996, has experimented with many literary genres, including writing texts for children’s books and picture books. Her literary breakthrough came with the young adult novel Speak (1999). When thirteen-year-old Melinda is raped at a disorderly party, she calls the police, but she cannot bring herself to talk about what happened. How can we speak about what the world refuses to see? How can we speak so that we will be heard and believed? Speak is a skilfully written, informed depiction of how rape survivors experience stigmatization as a result of emotional and physical bullying. Because Melinda has broken the code of silence, she is rejected by her best friend and ostracized from school social life. Her strategy for surviving the pain, shame, and isolation is to stop speaking.

The title Speak is meant to be read as a call to action. Speak so that the world will listen: “speak up for yourself.” Anderson’s novel was published long before #MeToo and had an enormous impact. The part it has played in encouraging survivors – regardless of gender – to come forward and speak about their experiences of sexual assault has been widely acknowledged. Speak has been translated into many languages and has been adapted as a graphic novel with illustrations by Emily Carroll (2018). It has also been adapted for film (2004). Like many of Anderson’s books, it is frequently found on lists of banned books: books that, in some states or districts in the United States, are not allowed to be read in schools or bought by public libraries because of their subject matter or plot. One of the poems in Shout is about an encounter between the author and a school librarian who cannot order Speak for the library because it would put her job on the line.

Another often banned book is Twisted (2007), a penetrating and sensitive investigation into the challenges and limitations of masculinity, told from the perspective of the headstrong teenager Tyler Miller. When Tyler defaces school property with graffiti, his punishment is to do hard physical labour: something that literally transforms him in both body and soul. Twisted can be described as an updated version of J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, but at the same time it is also different. Tyler is a soul-searching, often keenly perceptive first-person narrator, much like Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, but his voice also conveys a gloomy cheerfulness combined with growing desperation about his relationships to his family, his father, and the prettiest girl at school. One example is the careful list he makes of various alternatives to suicide, noting the advantages and disadvantages of each. Another is his discussion with a teacher about how to interpret Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus and the question of selling one’s soul to the devil. That Salinger is one of the authors Anderson relates to becomes clear in Shout, where one of the poems is entitled “Salinger and Me.”

Several of Anderson’s young adult books are set in and around high schools—besides Speak, this applies to novels such as Catalyst (2002), Prom (2005), and Twisted—but this specific setting simultaneously functions as a mirror of the world outside school. Anderson typically allows places or spaces to reflect feelings, utterances, and moods. In Speak, the ostracized Melinda takes refuge in a janitor’s closet; in Wintergirls, the main character returns again and again to the hotel room where her friend died, and ultimately she too isolates herself there. The sometimes obsessive tendency in Anderson’s adolescent characters often stems from their belief in an idea or from unfailingly following their own path. This applies, for example, to Kate Malone in Catalyst, who is set on getting into a prestigious university, and Tyler Miller in Twisted, who does not want to conform to society’s norms. Anderson’s young adult novels display a striking sensitivity to individual integrity.

Obsession can also extend to a compulsion to control the body, as in Wintergirls (2009), a harrowing and detailed documentation of two girls’ life-threatening eating disorders, including calorie counting and self-harming behaviours. Lia and Cassie start out as friends, but their struggle to be as thin as possible has left them frozen inside their bodies. Anderson makes the issue of self-control concrete and tangible by literally striking through occasional words, names, and thoughts that appear on the pages of the book—as if they are the fragmentary innermost thoughts and desires of Lia, the narrator, that she wants to keep secret or severely repress. Anderson’s prose is rich with imagery and often leans on literature and myth. Wintergirls references the story of Sleeping Beauty and, even more strongly, the myth of Perspehone. In the myth, Persephone is taken to the underworld by Hades, ruler of the dead, and only allowed to return to the surface in the summer months. The myth forms a telling parallel to the winter girls, who also balance between life and death. Lia survives a suicide attempt and finds a way back from her illness, while Cassies dies from her bulimia.

The role of time and memory in young adult development is a major narrative force in The Impossible Knife of Memory (2014). Hayley and her father have moved back to the city she grew up in so that Hayley can finish school there. The father is a war veteran who has PTSD and abuses alcohol in order to repress painful memories. Hayley has to be the grown-up in the family. She lives in a state of constant worry about her father and hides her difficult situation from her school and the authorities. Although she describes her daily life, school friends, and the adult world with cynicism and a dry, dispassionate wit, it is obvious that Hayley is repressing difficult memories from her childhood. Not until she meets Finn—who wins her trust—can she finally begin to process her experiences.

Anderson’s first historical novel was Fever 1793 (2000), a story about the yellow fever epidemic in the United States in the late eighteenth century. But her greatest historical project is the trilogy Seeds of America, which includes the books Chains (2008), Forge (2010), and Ashes (2016). The trilogy opens in 1776, the year of the Declaration of Independence, and unfolds during and after the period of the American Revolution: the conflict between the English and the Patriots that led to a number of Eastern states breaking free from British rule and forming the United States of America. The trilogy ends in 1781. At its centre is Isabel, a 13-year-old enslaved girl. Both she and her sister have been promised their freedom in their enslaver’s will. But instead Isabel is sold at auction and separated from her sister. When she meets Curzon, an enslaved boy, she is recruited to spy on her enslavers, who have information about the British plans to invade. In Forge, the narrative perspective shifts to Curzon and his experience fighting in the Patriot army. Ashes focuses increasingly on Isabel’s and Curzon’s dream of living in freedom and their search for Isabel’s missing sister, Ruth. American history is thus shown through the eyes of both children: Isabel, the first-person narrator of the first and third books, and Curzon, the first-person narrator of the second book.

Seeds of America is an impressive picture of a society and an era. It reflects Anderson’s burning interest both in the history of America and in the ways that individual destinies are formed. Each chapter opens with a quotation that anchors the story in time. These authentic fragments of text form a choir of historical voices ranging from governors, politicians, officers, and enslavers to enslaved people, Patriot soldiers, and abolitionists. The trilogy builds on extensive research and seamlessly incorporates various forms of documentary evidence, including excerpts from letters, testimonies, diaries, and newspaper articles. One example is a newspaper advertisement from 1776 about an enslaved freedom seeker. Another is an excerpt from a petition for freedom addressed to the Massachusetts governor by a group of enslaved people in 1774. Each book in the trilogy includes an appendix with information about the historical events and the genesis of the trilogy, including references and suggestions for further reading.

It has been said of Laurie Halse Anderson that “her books have changed lives,” and many people have testified to the significance of her work. That she maintains an open, intensive dialogue with her readers is clear. Two decades after its publication, Speak was reissued in an anniversary edition in 2019. In the same year, Anderson published Shout, her memoir-in-verse in which she writes about her own upbringing and how she found her way to books, reading, and language. In her introduction to the book, Anderson writes, “This is the story of a girl who lost her voice and wrote herself a new one.” She uses the form of the poetic memoir to call up her own memories and experiences, a process that connects to her other published works. Like Melinda in Speak, Anderson was raped at the age of 13, an act of violence that affected both her life and her work as an author. Shout is the lyric counterpart to Speak, and, as its title emphasizes, daring to speak is not enough. To survive, you have to shout. “The only thing that helped me breathe/ was opening a book,” writes Anderson in one of the poems. And the closing lines of the poem “#MeToo’” leave no doubt about what the author wants to say: “Me to be stronger / you to stand taller / we to shout louder / than they thought / we could”.

In the writing of Laurie Halse Anderson, the yearning for love and belonging is a recurring theme, and in her texts she evokes conditions, moods, and emotions with arresting intensity. But her darkly radiant realism never shies from even the hardest things.

The only thing that helped me breathe was opening a book

Acceptance Speech

"Literature brings light to all of us in dark times. Throughout history, across countries and cultures, people have used stories to prepare their children for the world that they will inherit. Stories open the doors to conversation and growth. Books strengthen us and help lay the foundations of morality and wisdom."

The full Acceptance Speech

"Writing helps me make sense of the world"

Where does Laurie Halse Anderson get her inspiration? When did she know that she wanted to be a writer, and what was she like as a teenager? Read our interview with this year's laureate!

Read our interview with the 2023 LaureateLaurie Halse Anderson in conversation with culture writer Johanna Lundin. Filmed at Kulturhuset Stadsteatern in Stockholm, Thursday 4 May, 2023.

Discover our laureates

The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award is awarded to authors, illustrators and narrators, but also to people or organizations that work to promote reading.

Find out more about the laureates

Children have the right to great stories

To lose yourself in a story is to find yourself in the grip of an irresistible power. A power that provokes thought, unlocks language and allows the imagination to roam free. The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was created in 2002 by the Swedish government to promote every child’s right to great stories.

Find out more about the award