Photo: Maja Brand

Photo: Maja Brand“We need to take children’s literature more seriously”

How does Maron Brunet succeed in writing about social problems without becoming propagandistic? What does her selection for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award mean to her, and how does she think children’s literature is treated in her native France? Our jury member Lena Kåreland spoke with the 2025 Laureate.

You have received a number of literary awards in France. What does your selection for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award mean to you?

– It means a huge amount to me to receive this international prize, the world’s largest children’s book prize, from among so many nominees. Being selected for for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award represents a major recognition of me and my work and it is also of importance for children’s literature in general. My hope is that the award can help raise the status of children’s books in France.

Do you have a favourite Astrid Lindgren character?

– I confess I haven’t read all of Astrid Lindgren’s books. But when I was little, I loved That boy Emil. However, I didn’t read Pippi Longstocking. But I feel great respect for Astrid Lindgren’s core values and solidarity with them. Her sense of equality, her devotion to the natural world—so many of her values are mine as well.

Why is children’s and youth literature important and what kind of treatment does it receive today—in your home country of France, for example?

– Books for children and young people play a central role in their lives. It broadens their experiences and brings them in contact with art. But in France, we need to take children’s literature more seriously. We need to put it on a level with adult literature. We have a long way to go. Some people only read my books for adults and never my YA books. The same themes and concerns run through everything I write, but they don’t want to see it.

The environment, especially the natural world, is important in your writing. What are your thoughts on nature and its role in your books?

– What I think is quite important, and try to communicate in my stories, is the relationship between physical sensations and nature. The body is central and part of an interaction between the external and the internal worlds. Humans are affected by nature, emotionally and also purely physically. Some readers say they actually got seasick from reading Plein gris. And in L’été circulaire, the oppressive heat and the broiling sun directly influence what the characters do. I try to show how feelings like heat or cold, as well as desire, fear, and anger, have a tight connection to nature and the body. Nature is an integral element of my narratives.

Photo: Maja Brand

Photo: Maja Brand

Most of your books are set in the present day and address issues of current concern, such as climate change, poverty, or social inequality. But your writing is never agitational or propogandistic. How do you do it?

– I hope that I never propagandize for any particular point of view. What I want is to show readers how things can look in our world, so that they have an opportunity to ask their own questions. Ultimately, my words are there to help readers find their own path. As a writer, it’s also important to me to not be too pathos-laden, and I try to avoid being sentimental.

Plein gris is a hugely suspenseful novel. In this story, which is set on a yacht, the very first sentences establish the dramatic tension. One of the five teen characters has been found dead in the water. What happened? Do you plot out your books before you start writing, or do the twists and turns develop as you go along?

– I tend to have a good general outline, but I avoid working out the entire plot in too much detail. But there are exceptions. For my novels of suspense, like Plein gris and La Gueule du loup, I know exactly how the story will unfold, chapter by chapter, from the start.

There are many young protesters in your books. For example, Dans le désordre features a group that unites around the desire for a better world. Like many of your books, this one revolves around a collective. But it also features a tender love story that counterbalances the book’s very dramatic and violent scenes. Do you often work with contrasts in this way when you compose your books?

– No, I wouldn’t say that. Rather, I try to work with language to create a balance in my narratives. I try to shift between different registers. I may write a poetic or quiet passages—often, descriptions of nature have this function—and follow it with a passage that has a rawer tone, that is intense, brutal, or violent. I use these juxtapositions to try and achieve rhythm and variation in the narrative.

What I want is to show readers how things can look in our world, so that they have an opportunity to ask their own questions. Ultimately, my words are there to help readers find their own path.

You’re not a traditional YA writer. School, for example, doesn’t feature prominently in your books. But Des rire des hyènes does revolve around a teacher—one who fails utterly when they try to convey their passion for literature to their students. It’s a powerfully charged story and the resolution, when it arrives, feels like a punch in the stomach. What do you say about this book’s ending?

– Des rire des hyènes is an outlier among my books. I thought it would make for an interesting challenge to flip the perspective and have the subject of the bullying be a teacher, instead of a student. It allowed me to tell a different kind of story. Certainly, the ending is far from what you could call moralistic. But what I want to show is that teachers are people, too. And when they are subjected to too much psychological distress and pressure, you don’t know what will happen. You can lose your grip completely, take actions that are uncalled for. Reason gets left behind; emotion takes over. I’ve been fascinated to see the classroom discussions this book has sparked. The teacher’s situation and actions have given rise to some passionate debates.

What is your relationship to the French narrative tradition? I see you as a writer in the tradition of Victor Hugo—I’m thinking of his civic engagement, how he stood up for the vulnerable and those on the lowest rung of the social ladder. Alexandre Dumas also comes to mind, with his ability to create suspense and adventure.

– Oh, I loved Dumas when I was growing up. The Three Musketeers! I read it so many times. Friendship is also so central in that book, something which probably has inspired me in my own writing. Friendships of different kinds, as well as solidarity to the group, play a central role in a number of my books. When it comes to Hugo, I’m drawn less to his novels than his poems, which I’ve read more of. His poems about the poor and vulnerable have spoken to me the most. He wrote a number of poems about conditions for miners. One of the most famous is “Ode à la misère”, and I was very moved by it when I read it as a child. I’d also mention another classical author who has been important for me: Guy de Maupassant. He is an exceptional writer who addresses social differences and injustices with precision and great finesse. His novels have been a lasting influence.

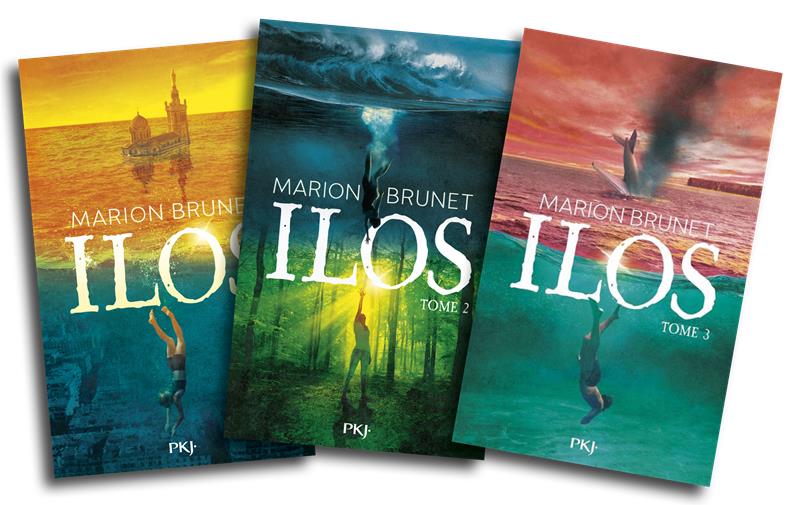

You mainly write realistic, contemporary novels. One exception is Sans foi ni loi, set in the nineteenth-century United States. But sometimes you also allude to myth and folk tale, especially in your ongoing trilogy, Ilos. In this dystopia, I think I see Greek mythology in the background, and the characters are clear-cut, as in folk tales. It’s a story of good versus evil—again, like a folk tale. Was this in your mind when you planned the story?

– No, I wasn’t thinking along those lines, at least not consciously. When it comes to Ilos, I suspect it’s the genre itself—the near-future dystopia—that produces some of the mythological and folk patterns. Speaking of mythology, a reader once pointed out that Dans le désordre has the same structure as a Greek drama. But I certainly didn’t set out to follow the Classical dramatic template. On the other hand, what is important to me in both books—as in so much of my writing—is the idea of the collective. The collective is closely bound up with friendship, and in a world where the social climate keeps getting harsher, and individualism is so strong, groups are important. We need to come together in friendship and solidarity. It is in the collective that I can see a glimmer of hope for a better future.

I keep coming back to your book Vanda, where you write about a young boy—just six years old—and his mother. The story of Vanda and her son, so alone and vulnerable in the world, is deeply moving. The blue Mediterranean is also a constant presence. The book’s final sentence reads: “You and me, and the blue. You and me against the rest of the world.” In a way, these words represent you as an author. Loneliness, abandonment, the small and powerless against the rest of the world, humans against nature. Was that in your mind?

– Yes, you could say that. Vanda has a very tragic ending, an ending that matches the state of the world today. The closing words express great sadness and great loneliness. “The small and powerless against the rest of the world”—yes, I’d agree that’s a consistent theme in my writing. For me, though, it’s never humans against nature. Quite the reverse.

Interview by Lena Kåreland.

Shimmering and crystal-clear prose

Marion Brunet is a French author whose first novel, "Frangine" (Sister), was published in 2013. In her books, Brunet spotlights burning social issues and draws insightful portraits of vulnerable groups and young people in revolt. She is timely in her choice of topics, timeless in her linkages to folkore and myth.

Discover Marion Brunet