On Astrid’s 90th birthday, letters from well-wishers filled 15 mailbags, sent by thousands upon thousands of readers whose lives she had made richer with her stories. Astrid herself always claimed that she wrote for the child she had been, and the child she remained inside. She had a unique ability to remember how children think and feel and to convey that insight to readers of all ages and backgrounds.

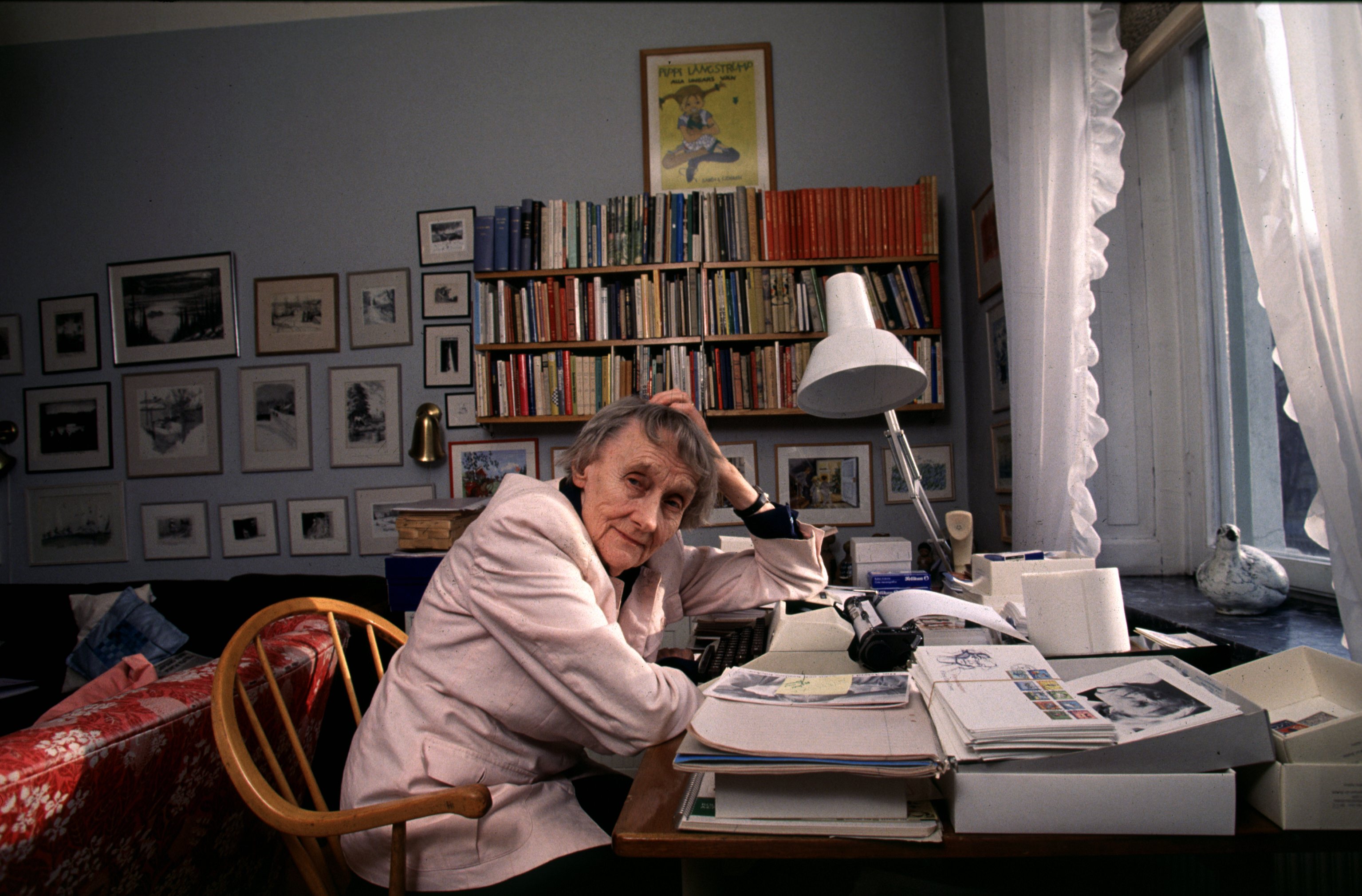

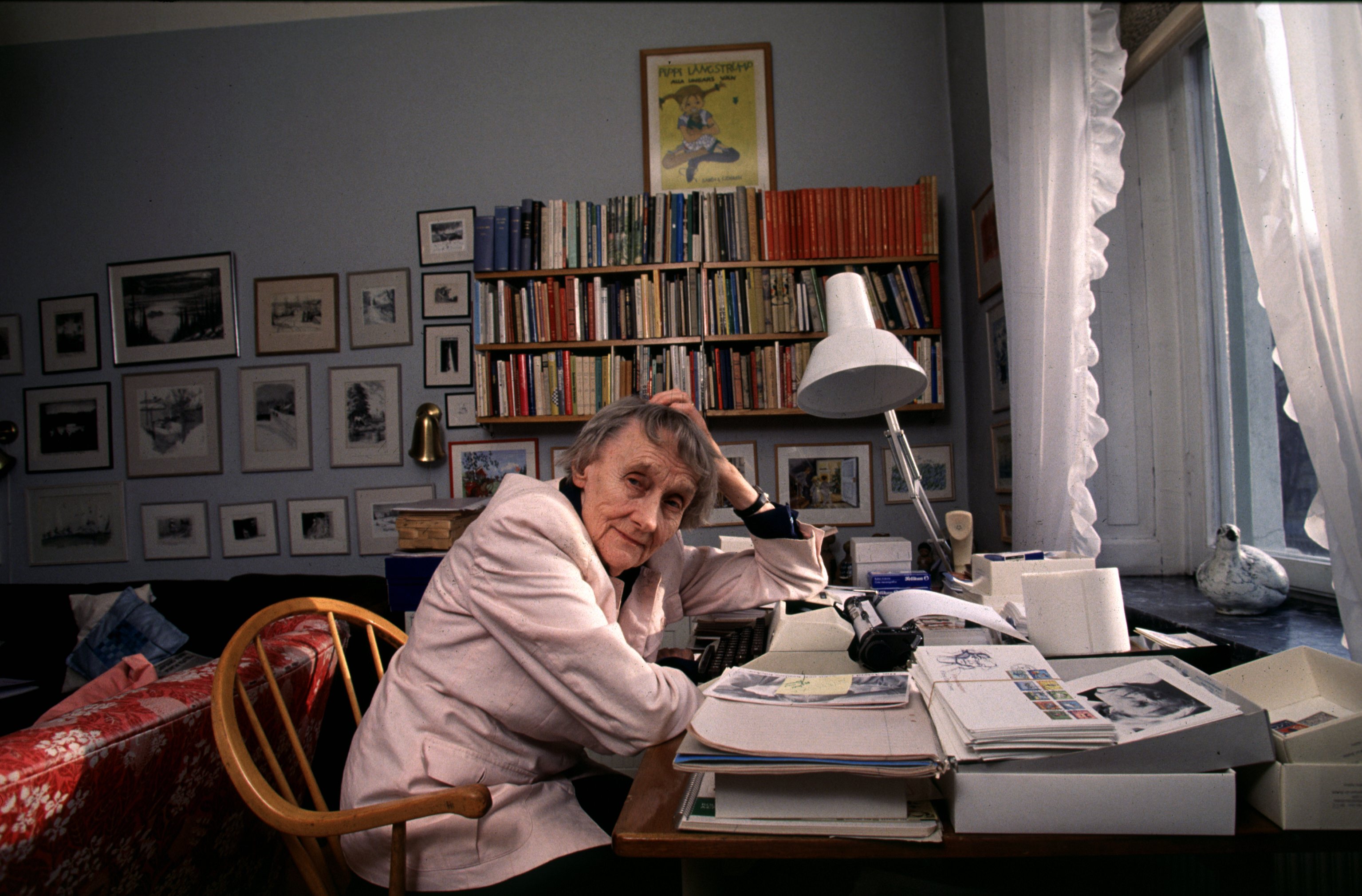

Astrid Lindgren in her apartment at Dalagatan in Stockholm, 1992. Photo: Charles Hammarsten/IBL Bildbyrå

Astrid Lindgren in her apartment at Dalagatan in Stockholm, 1992. Photo: Charles Hammarsten/IBL Bildbyrå

Astrid Anna Emilia was born on November 14, 1907 (November 14 is the “name day” for the name Emil) as the second child of Hanna and Samuel August, on Näs Farm just outside the small town of Vimmerby in Småland. She had a brother, Gunnar, one year older than she. Later two more sisters, Stina and Ingegerd, would be born. Astrid showed readers her childhood in her books about Bullerby Village, a childhood filled with fun and games, love and security. Her teenage years were more melancholy and searching, punctuated by very real rebellions against the narrow-mindedness of her small town. She returned to those experiences in the Mardie books, criticizing the way society judges people based on social and economic status. She herself was democratic to the core, treated everyone equally—children, heads of state, bus drivers.

Astrid moved to Stockholm at age 18. She took secretarial classes, and after a few years, she married Sture Lindgren. But it had always been clear, as a schoolchild and later as a volunteer for the local paper in Vimmerby, that she had a gift for writing. As a young mother, Astrid began to write nursery tales and short stories to earn extra money. On September 1, 1939, the day World War II broke out in Europe, she started a war diary. In it she reflected on world events as well as her own family life; the Battle of Stalingrad and the occupation of Denmark and Norway entangle with her her worry over her son’s grades and her daughter’s cold, in a profoundly humane way. This unique historical record was published in 2015 (in Swedish as Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945, Salikon).

Astrid Lindgren, 1953. Photo: SvD / TT

Astrid Lindgren, 1953. Photo: SvD / TT

During the war, Astrid also began make up stories for her daughter Karin about a little girl with a curious name that Karin had invented—Pippi Longstocking. Then she started to write the stories down, The first Pippi book was published in Sweden at the Christmas season in 1945. It was like no children’s book anyone had ever read and was an immediate commercial success. Bookstores quickly sold out of it. One critic heralded it as the children’s book of the century. Others called it a revolution in the nursery. Of course not everyone was equally charmed; Sweden’s first professor of education thought Pippi “an unpleasant thing that scratched at one’s soul” and “behaved as if she was mentally ill.” Fortunately, children care little for the pronouncements of professors. The very next year, Pippi set off on her triumphal progress round the globe. In the years since, multitudes of people have testified to her importance as a role model for generations of girls: a character who dared to stand up to restrictive rules and oppression and forge her own path in life. Pippi Longstocking became a feminist icon the world over. Even today, she challenges and tests adults in their views on the rights of young girls—and all children.

Just like Pippi—if not quite as provocatively—most of Astrid Lindgren’s characters still spread their creator’s message: that children have the right to be treated with respect and love, and adults have the obligation to meet their fundamental needs, for food and shelter but also for attention, loving care, security, and stimulation of mind and body. Never, throughout her long life, did Astrid waver in her focus. In book after book—and from movie screens and theater stages—her message was repeated.

Astrid was not only an author but also a book editor. She spent 25 years encouraging writers, ushering in what has been called a second Golden Age for Swedish children’s literature. She opened the door to the international successes that Swedish children’s culture and literature experienced in the late 20th century, and she followed and nurtured many writers, sometimes from a shaky beginning. The 2014 ALMA laureate Barbro Lindgren was just one of them.

Astrid herself was firmly rooted in the culture of a Swedish peasant culture that has long since disappeared. But she had a genuine feeling for the things that unite humanity across time and space. Her books convey joy and comfort, good cheer and hope for people from all corners of the earth. In a quite marvellous way, she spoke straight to children in South Africa, Brazil, Greenland, Korea—and to all of us who used to be children ourselves, and haven’t quite forgotten how it felt.

Astrid Lindgren reading a book for her grandchildren, 1965. Photo: Ulf Stråhle / SVT

Astrid Lindgren reading a book for her grandchildren, 1965. Photo: Ulf Stråhle / SVT

At a time in life when people often tend to settle in and take stock, this curious woman instead began a new phase of her existence. Astrid had always been a keen observer of society; her war diaries are resounding proof of that. Now she began to contribute to the public debate, making headlines into the 1990s on a diverse range of topics: the Vietnam War, refugee children, animal welfare, nuclear power, tax injustice, neo-Nazism, the European Union, and urban planning, to name a few. Always, her concerns centered on our children and their future.

When Astrid died in 2002 all of Sweden mourned, alongside millions of admirers around the world. Some 100,000 people lined the streets for her funeral procession. The Swedish royal family and the Government were represented in the church. So too—and above all—were her readers. The voice that had always told us how important it was to be “a human being, not just a piece of dirt” had fallen silent. Astrid Lindgren represented Sweden at its best and most humane.

Text: Lena Törnqvist, literary scholar and librarian

Read more about Astrid Lindgren on the official website.

Photo: Roine Karlsson

Photo: Roine Karlsson

Astrid Lindgren in her apartment at Dalagatan in Stockholm, 1992. Photo: Charles Hammarsten/IBL Bildbyrå

Astrid Lindgren in her apartment at Dalagatan in Stockholm, 1992. Photo: Charles Hammarsten/IBL Bildbyrå Astrid Lindgren, 1953. Photo: SvD / TT

Astrid Lindgren, 1953. Photo: SvD / TT Astrid Lindgren reading a book for her grandchildren, 1965. Photo: Ulf Stråhle / SVT

Astrid Lindgren reading a book for her grandchildren, 1965. Photo: Ulf Stråhle / SVT